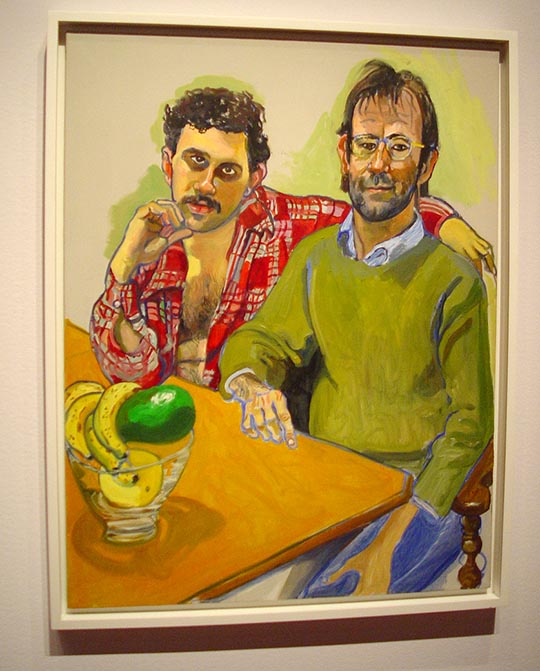

When SFMOMA reopened in 2016 after its huge expansion, I saw the painting above for the first time, and it stopped me dead in my tracks. The casual yet penetrating depiction of a gay couple (Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, 1978) sitting at a kitchen table while staring back at the viewer, was unlike anything else in the museum. The artist, Alice Neel, was completely unknown to me, but I instantly became a member of her admiring cult.

Alice Neel (1900-1984) was desperately poor and unappreciated artistically most of her life for a number of reasons: her gender, her figurative style when abstraction was the fashion, her domicile in New York's Spanish Harlem when the art scene was centered in Greenwich Village, and her sincere far-left politics bred during the 1930s Depression. She was also, like most great painters, an egomaniac who had her own vision. In 1974, she was finally given a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and spent her last decade as a minor celebrity, even appearing on the Johnny Carson show a couple of times. The power of her work, however, is finally being recognized at the highest institutional level, with a major show last year at the Metropolitan Museum in New York which has now traveled to the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

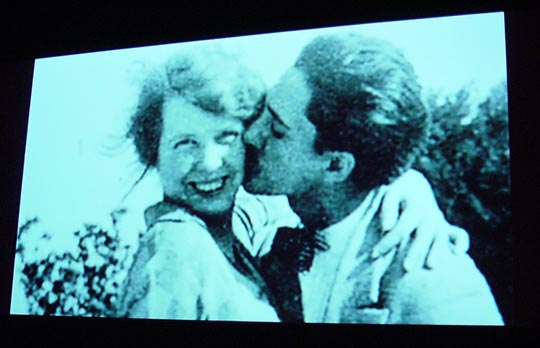

A couple of weekends ago, Andrew Neel brought his 2007 documentary about his grandmother, Alice Neel, to the deYoung Museum, and it was a fascinating work of art on its own. (You can watch it on Amazon Prime, which is highly recommended if you are planning on seeing the exhibit.)

Alice was from a working-class Pennsylvania family who went to a Women's Art School in Philadelphia. At a summer school, she met the upper-class Cuban art student Carlos Enriquez, married him and had a daughter.

This did not thrill Enriquez's Cuban family. While the couple were trying to make their way as starving artists in 1920s New York, their daughter died of diphtheria. When another daughter, Isabetta, was born, Carlos took her to Cuba and left the child with his parents while he took off for Paris. (The painting above is the 1926 portrait, Carlos Enriquez.)

The abandoned Alice went into a suicidal, clinical depression. After a few unsuccessful suicide attempts, and a year in a Philadelphia mental institution, Alice decided that "I could jump out a window or just serve my time," and she decided to live. That included hooking up with a young Puerto Rican musician, who is in the 1936 portrait, Jose Santiago Negron.

In 1939, she had a son by him, Richard, and a couple of years later Hartley was born during her union with the Communist documentary filmmaker Sam Brody. The painting above is Hartley and Richard, 1950.

The two important things parents can do for their children are to give them love and to make them feel safe. From the accounts in Andrew's very frank family documentary, there was plenty of the former but not much of the latter, with Richard getting the worst of it via constant bullying from Sam Brody. Richard is pictured above in a 1963 portrait.

It's not particularly surprising that Richard rebelled at the Bohemian world he had grown up in and became a Nixon-loving corporate lawyer for Pan Am. Alice was not amused, and painted the rather cruel portrait above, Richard in the Era of the Corporation (1978-79).

Hartley, shown above in a 1966 portrait, became a radiologist.

Alice's bohemianism extended to her frankness about nudity and sex, in pictures that are still shocking, like the 1935 Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom).

Her portrait of the art critic John Perreault is both erotic and funny. In an essay on the painter Joan Mitchell, Perreault writes: "“Her Fifth Sin,” he wrote of Mitchell, “was that she didn’t have a wife to promote her and steady the helm. Wild woman Alice Neel once told me, when I was posing naked for her, that she would have been famous much sooner if, like Jackson Pollock, she had had Lee Krasner for a wife, or like de Kooning she had had an Elaine.”

Neel's series of portraits of pregnant women are unlike any other before or since, without a hint of sentimentality. (Above is the 1964 Pregnant Maria)

Alice had problems with the feminist movement, noting that it was mostly run by white bourgie women, but the movement benefited her immensely at the end of her life. Pictured above is the echt-1972 Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), with its still slightly shocking tuft of armpit hair confronting the viewer.

Alice painted portraits of every type of person imaginable: the rich, poor, famous, nobodies, family, and strangers. In 1971, she invited the San Francisco concert pianist Robert Avedis Hagopian (1945-1984) to her home studio and painted the portrait above. He was one of the many eventual AIDS casualties that figure among her sitters, including the Detroit-born artist Brian Buczak who is in the first photo of this post. Alice kept this painting until her own death, which was then bought by the Hagopian family, and which is now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

She only painted one self-portrait, and waited until the age of 80 where she casually, defiantly, and subversively lets it all hang out. She looks like an old Irish grandmother who is somehow stronger than anybody else in the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment