The producer and director Russell Blackwood often cast himself in a small, juicy role in most of his revivals of Cockettes musicals that The Thrillpeddlers presented at the legendary Hypnodrome on 10th Street in San Francisco. In a recent interview, he told me his favorite was probably Madame Fu from Pearls Over Shanghai, the first, deliriously successful Cockettes revival the company presented for almost two years.

My favorite of his cameos was in the next Cockettes musical the group presented, Hot Greeks, an inspired mashup of Aristophanes' Lysistrata and June Allyson MGM college musicals. He played the oracle MataDildoes who sings one of Scrumbly Koldewyn's most perverse songs, The Hot Twat of Tangier. The lyrics and performer were a match made in theatrical heaven, and Mr. Blackwood will be pulling himself briefly out of retirement for a reprise on Saturday at the Victoria Theater where the Cockettes' 50th anniversary show will be held.

Just about everyone in the large troupe had day jobs, including one of my other favorite Thrillpeddlers performers, Eric Tyson Wertz, whose other identity besides bizarrely beautiful ragpicking peasant girl was as a physicist.

Wertz out of costume was a beefy, hairy-chested guy, but there was a goofy, delicate sweetness in his playing of innocent young girls with deadpan sincerity, as he demonstrated in Hot Greeks as a cheerleader withholding sex from her athlete boyfriend.

The Hypnodrome's building was sold in 2017 and the Thrillpeddlers disbanded, so even though this Saturday's event is not being billed as a reunion, it will be the first time that Blackwood has gotten together with the gang to perform since then.

"Why now?" I asked Russell Blackwood, above left in a fabulous outfit from Vice Palace, a reworking of Poe's Masque of the Red Death set in 1960s high-fashion, La Dolce Vita Italy. "Because I revived Pearls of Shanghai for the Cockettes' 40th anniversary and this will be the 50th year since their first performance. I like anniversaries," he replied.

Vice Palace, though it was basically a string of unrelated numbers in different colored rooms, was dark and bizarrely prescient about the AIDS plague that was coming in the next decade. Though the association was never made explicit, it suffused the whole show.

The score by original Cockette and surviving Music Director Scrumbly Koldewyn (above, dressed somewhat formally) was a marvel, incorporating sophisticated riffs on Nino Rota soundtracks.

And how can one resist a musical that includes a novelty number called A Crab on Uranus, which will also be performed at this Saturday's grab-bag spectacular?

Monday, December 30, 2019

Sunday, December 29, 2019

Cockettes Are Golden 1

The Cockettes were a group of mostly gay male hippies in late 1960s-early 1970s San Francisco. They were a smart, arty, psychedelically druggy, genderfuck group of friends who for a short while were a theatrical sensation that influenced world culture in ways that are still being absorbed. (Pictured above left to right Pristine Condition, Marshall Olds, Miss Bobby, Danny Isley, Link Martin. San Francisco, 1971, photo by Fayette Hauser.)

Their midnight shows in a movie palace in North Beach, literally named The Palace, became an immediate cult hit, especially for audiences who were stoned on one psychedelic or another, and it attracted a few fabulous freaks from around the country, including John Waters' diva, Divine. (Clockwise from upper left: Billy Orchid, Divine, Scrumbly Koldewyn, Pristine Condition, Pam Tent, Mink Stole, David Baker, Jr. in "Vice Palace," 1972, Palace Theater in SF, photo by Clay Gerdes.)

This Saturday, January 4th, there will be a celebration at the Victoria Theater on 16th Street of the Cockettes' 50th Anniversary, in honor of their first performance on New Year's Eve in 1969. Saturday's event promises to be historic for a number of reasons, and if you take San Francisco culture seriously, you'll be there. I just went to the ticket site, however, and realize that everyone who is anyone knows about this already and it has sold out. Start begging friends for extra tickets.

The Cockettes only lasted about three years before imploding and splintering into other groups like the 1970s Angels of Light, which had fabulous sets and costumes but not much of the Cockettes' outrageous wit. The group became a distant legend until a 2002 documentary by David Weissman and Bill Weber told their story to a wider audience. The Cockettes' real revival, however, arrived at a little theater in the back of an antique store under the South of Market freeway next to Costco. Russell Blackwood was offered the space in 2004 for very little money by the owners of the building because they were fans of his theatrical work which at the time focused on a revival of French Grand Guignol.

In a never-used director's head shot for the 1991 Laboratory of Hallucinations, Mr. Blackwood is being serviced by a skeleton, while the gentleman on the left is Scrumbly Koldewyn, the composer and musical director for the Cockettes, when he was a young hippie performing in Pearls Over Shanghai as Lili Frustrata.br />

In 2009, the two seasoned theatrical geniuses gathered their varied groups of performing gypsies together and collaborated on a revival of a book-and-score musical performed by the Cockettes called Pearls Over Shanghai, which knowingly incorporated every Orientalist cliche from the 19th century through 1930s Hollywood about the Mysterious, Decadent East.

The show was supposed to run for two months at most, and ended up virtually selling out the place for the next 22 months. (Pictured above is the late-great Arturo Galster as Madame Gin Sling). More to come about the gay, leftist, hippie, all-gender-inclusive gestalt that characterized both the Cockettes and the Thrillpeddlers, who will be performing for the first time in three years together, and possibly the last time too.

Their midnight shows in a movie palace in North Beach, literally named The Palace, became an immediate cult hit, especially for audiences who were stoned on one psychedelic or another, and it attracted a few fabulous freaks from around the country, including John Waters' diva, Divine. (Clockwise from upper left: Billy Orchid, Divine, Scrumbly Koldewyn, Pristine Condition, Pam Tent, Mink Stole, David Baker, Jr. in "Vice Palace," 1972, Palace Theater in SF, photo by Clay Gerdes.)

This Saturday, January 4th, there will be a celebration at the Victoria Theater on 16th Street of the Cockettes' 50th Anniversary, in honor of their first performance on New Year's Eve in 1969. Saturday's event promises to be historic for a number of reasons, and if you take San Francisco culture seriously, you'll be there. I just went to the ticket site, however, and realize that everyone who is anyone knows about this already and it has sold out. Start begging friends for extra tickets.

The Cockettes only lasted about three years before imploding and splintering into other groups like the 1970s Angels of Light, which had fabulous sets and costumes but not much of the Cockettes' outrageous wit. The group became a distant legend until a 2002 documentary by David Weissman and Bill Weber told their story to a wider audience. The Cockettes' real revival, however, arrived at a little theater in the back of an antique store under the South of Market freeway next to Costco. Russell Blackwood was offered the space in 2004 for very little money by the owners of the building because they were fans of his theatrical work which at the time focused on a revival of French Grand Guignol.

In a never-used director's head shot for the 1991 Laboratory of Hallucinations, Mr. Blackwood is being serviced by a skeleton, while the gentleman on the left is Scrumbly Koldewyn, the composer and musical director for the Cockettes, when he was a young hippie performing in Pearls Over Shanghai as Lili Frustrata.br />

In 2009, the two seasoned theatrical geniuses gathered their varied groups of performing gypsies together and collaborated on a revival of a book-and-score musical performed by the Cockettes called Pearls Over Shanghai, which knowingly incorporated every Orientalist cliche from the 19th century through 1930s Hollywood about the Mysterious, Decadent East.

The show was supposed to run for two months at most, and ended up virtually selling out the place for the next 22 months. (Pictured above is the late-great Arturo Galster as Madame Gin Sling). More to come about the gay, leftist, hippie, all-gender-inclusive gestalt that characterized both the Cockettes and the Thrillpeddlers, who will be performing for the first time in three years together, and possibly the last time too.

Wednesday, December 25, 2019

Eun Sun Kim and the Adler Fellows

An email invitation to attend an onstage Major Announcement was sent out by the San Francisco Opera earlier this month.

The most viable guess for the drama was that the company was announcing a new Music Director. Lisa Hirsch (above right) speculated at the Iron Tongue of Midnight blog who the top four contenders might be (either Eun Sun Kim, James Gaffigan, Christopher Franklin, or Henrik Nánási), and one of her hunches was correct.

The 39-year-old Eun Sun Kim, who conducted Dvorak's Rusalka in her company debut last summer, was chosen, a decision ecstatically received by many in the orchestra, chorus, backstage crew, and management, not to mention the conductor herself.

San Francisco Opera didn't have a Music Director for its first sixty years, relying on guest conductors with overall music direction dictated by the company's two General Directors: founder Gaetano Merola (1923-1953), followed by Kurt Herbert Adler (1953-1981), with both conducting the occasional production. Merola died before I was born, but I did hear Adler conduct a number of times in the 1970s, sluggishly and with an authoritarian streak towards performers that became infamous. The Music Director position was created in 1985, filled by Sir John Pritchard, who was at the end of a long, distinguished career at Covent Garden and Glyndebourne. He seemed bored by most of his assignments at the SF Opera, with a few notable exceptions such as an electrifying Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk with Josephine Barstow, and he died in 1989 at the relatively early age of 68. The young, energetic and fabulously talented Donald Runnicles took the helm in 1992 for the next 17 years and the overall musical quality of both orchestra and chorus rose inestimably, while Runnicles' own conducting abilities seemed to grow with each year. His successor, Nicola Luisotti (2009-2018), was hired on the basis of a sensational conducting job on a production of Verdi's La Forza del Destino, but just about everything after that felt like a slide downhill or inappropriate for his particular musical affinities.

The new General Director Matthew Shilvock made the announcement of Kim's appointment and filled in her biography briefly. She was born in 1980 in Seoul, South Korea where she studied composition at the Yonsei University. A professor was so impressed with her coaching a student production of La Boheme that he encouraged her to focus on conducting. She continued her studies in Germany, with a doctorate from the University of Music in Stuttgart. Her apprenticeship in various European opera houses began at Madrid's Teatro Real in 2008, and continued in houses throughout Germany.

In an onstage interview, she recounted the difficulty of her U.S. debut with a production of La Traviata at the Houston Grand Opera weeks after Hurricane Harvey flooded the city in 2017. The production moved to an improvised pop-up theater in the George Brown Convention Center and Kim conducted the orchestra from behind the performers on a circular stage, rather like SF Opera's productions at Bill Graham during the opera house's 1996 earthquake retrofit. The experience went well enough that the company immediately named her Principal Guest Conductor.

During the audience interview portion, I asked her if she had any particular affinity for certain composers, and she declined to name any favorites. A few other questioners asked a variation on the same question and the response was the same, basically that whoever she is studying and conducting at the moment is her favorite.

The following evening, Shilvock introduced Kim to the audience at the annual Adler Fellows The Future Is Now concert, which she had long been scheduled to conduct. This grab-bag of scenas and arias seemed a good way to hear how she navigated composers from Handel to Bernstein.

Unfortunately, she was faced with the same dilemma as in Houston, conducting the large SF Opera orchestra on the small Herbst Theatre stage with singers at her back, which necessitated a lot of neck-twisting and contortions to keep everyone together. (Production photos are by Kristen Loken.)

Within these constraints, she did a remarkable job of conducting, starting off with the best live rendition of Bernstein's Candide Overture that I have ever heard, making it sound more seriously soulful than satirical hijinks. Her Verdi was very good, she doesn't get Mozart at all (it's surprising how many great conductors share that blind spot), her Handel was pulsing and sublime, and her Puccini was extraordinary. Tenor SeokJong Back sang a very creditable Recondita armonia from Tosca and the orchestral accompaniment was so richly colorful that it made me reassess my boycott of Puccini operas.

The Adler program is a two-year residency at the SF Opera, performing smaller roles and covering lead singers, for young musicians about to make their way into a professional career. My favorite performer of the evening was graduating baritone Christopher Pursell who was all Russian brooding in an aria from Rachmaninoff's obscure opera, Aleko, and then sang a funny, swaggering bit of bragadaccio about war and women from another obscurity, Thomas' comic French opera Le caïd.

The programming for these annual Adler concerts has always been weird, with operatic standards in every language surrounded by obscure French fluff. After intermission, for instance, we were offered arias from a Rossini French opera (Le Comte Ory), Massenet's Cendrillon and Le Cid, Berlioz's Les Nuits d'Ete, Thomas's Le caïd, and Donizetti's French opera La Fille du Regiment (pictured above, with soprano Natalie Image doing a good job rallying the troops).

Other favorite moments were first-year tenor Zhengyi Bai singing Le Postillon de Lonjumeau by Adam, a funny piece where a handsome young postman is plucked for his qualities by a queen to be king. First-year Adlers, soprano Mary Evelyn Hangley as Elisabetta and Christopher Colmenero as Don Carlo, have huge, rich voices which they demonstrated in a duet from Verdi's Don Carlo. Countertenor Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen astonished everyone the first time he opened his mouth as a Merolini three years ago, and he continued astonishing with a gloomy aria from Handel's Siroe.

Good luck to all of them in their careers, and welcome, Eun Sun Kim, to the San Francisco Opera. May the union between company and music director be a harmonious one.

The most viable guess for the drama was that the company was announcing a new Music Director. Lisa Hirsch (above right) speculated at the Iron Tongue of Midnight blog who the top four contenders might be (either Eun Sun Kim, James Gaffigan, Christopher Franklin, or Henrik Nánási), and one of her hunches was correct.

The 39-year-old Eun Sun Kim, who conducted Dvorak's Rusalka in her company debut last summer, was chosen, a decision ecstatically received by many in the orchestra, chorus, backstage crew, and management, not to mention the conductor herself.

San Francisco Opera didn't have a Music Director for its first sixty years, relying on guest conductors with overall music direction dictated by the company's two General Directors: founder Gaetano Merola (1923-1953), followed by Kurt Herbert Adler (1953-1981), with both conducting the occasional production. Merola died before I was born, but I did hear Adler conduct a number of times in the 1970s, sluggishly and with an authoritarian streak towards performers that became infamous. The Music Director position was created in 1985, filled by Sir John Pritchard, who was at the end of a long, distinguished career at Covent Garden and Glyndebourne. He seemed bored by most of his assignments at the SF Opera, with a few notable exceptions such as an electrifying Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk with Josephine Barstow, and he died in 1989 at the relatively early age of 68. The young, energetic and fabulously talented Donald Runnicles took the helm in 1992 for the next 17 years and the overall musical quality of both orchestra and chorus rose inestimably, while Runnicles' own conducting abilities seemed to grow with each year. His successor, Nicola Luisotti (2009-2018), was hired on the basis of a sensational conducting job on a production of Verdi's La Forza del Destino, but just about everything after that felt like a slide downhill or inappropriate for his particular musical affinities.

The new General Director Matthew Shilvock made the announcement of Kim's appointment and filled in her biography briefly. She was born in 1980 in Seoul, South Korea where she studied composition at the Yonsei University. A professor was so impressed with her coaching a student production of La Boheme that he encouraged her to focus on conducting. She continued her studies in Germany, with a doctorate from the University of Music in Stuttgart. Her apprenticeship in various European opera houses began at Madrid's Teatro Real in 2008, and continued in houses throughout Germany.

In an onstage interview, she recounted the difficulty of her U.S. debut with a production of La Traviata at the Houston Grand Opera weeks after Hurricane Harvey flooded the city in 2017. The production moved to an improvised pop-up theater in the George Brown Convention Center and Kim conducted the orchestra from behind the performers on a circular stage, rather like SF Opera's productions at Bill Graham during the opera house's 1996 earthquake retrofit. The experience went well enough that the company immediately named her Principal Guest Conductor.

During the audience interview portion, I asked her if she had any particular affinity for certain composers, and she declined to name any favorites. A few other questioners asked a variation on the same question and the response was the same, basically that whoever she is studying and conducting at the moment is her favorite.

The following evening, Shilvock introduced Kim to the audience at the annual Adler Fellows The Future Is Now concert, which she had long been scheduled to conduct. This grab-bag of scenas and arias seemed a good way to hear how she navigated composers from Handel to Bernstein.

Unfortunately, she was faced with the same dilemma as in Houston, conducting the large SF Opera orchestra on the small Herbst Theatre stage with singers at her back, which necessitated a lot of neck-twisting and contortions to keep everyone together. (Production photos are by Kristen Loken.)

Within these constraints, she did a remarkable job of conducting, starting off with the best live rendition of Bernstein's Candide Overture that I have ever heard, making it sound more seriously soulful than satirical hijinks. Her Verdi was very good, she doesn't get Mozart at all (it's surprising how many great conductors share that blind spot), her Handel was pulsing and sublime, and her Puccini was extraordinary. Tenor SeokJong Back sang a very creditable Recondita armonia from Tosca and the orchestral accompaniment was so richly colorful that it made me reassess my boycott of Puccini operas.

The Adler program is a two-year residency at the SF Opera, performing smaller roles and covering lead singers, for young musicians about to make their way into a professional career. My favorite performer of the evening was graduating baritone Christopher Pursell who was all Russian brooding in an aria from Rachmaninoff's obscure opera, Aleko, and then sang a funny, swaggering bit of bragadaccio about war and women from another obscurity, Thomas' comic French opera Le caïd.

The programming for these annual Adler concerts has always been weird, with operatic standards in every language surrounded by obscure French fluff. After intermission, for instance, we were offered arias from a Rossini French opera (Le Comte Ory), Massenet's Cendrillon and Le Cid, Berlioz's Les Nuits d'Ete, Thomas's Le caïd, and Donizetti's French opera La Fille du Regiment (pictured above, with soprano Natalie Image doing a good job rallying the troops).

Other favorite moments were first-year tenor Zhengyi Bai singing Le Postillon de Lonjumeau by Adam, a funny piece where a handsome young postman is plucked for his qualities by a queen to be king. First-year Adlers, soprano Mary Evelyn Hangley as Elisabetta and Christopher Colmenero as Don Carlo, have huge, rich voices which they demonstrated in a duet from Verdi's Don Carlo. Countertenor Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen astonished everyone the first time he opened his mouth as a Merolini three years ago, and he continued astonishing with a gloomy aria from Handel's Siroe.

Good luck to all of them in their careers, and welcome, Eun Sun Kim, to the San Francisco Opera. May the union between company and music director be a harmonious one.

Thursday, December 05, 2019

Ars Minerva's "Ermelinda" Revives the Italian Renaissance

Ars Minerva presented its fifth annual opera production, rediscovered from the Venetian library vaults, and the troupe under founder Céline Ricci just keeps getting more accomplished each year. The 1680 Ermelinda, composed by Domenico Freschi with a libretto by Francesco Maria Piccioli, was originally presented as a lavish musical entertainment for a Polish prince at a country palazzo. 440 years later it was receiving its second set of performances at the tiny ODC Dance Theater in the Mission District of San Francisco in what felt like a feat of time travel. The piece is anchored by a love trio involving contralto Sara Couden as the nobleman Ormondo who spends much of the opera posing as the lower-born Clorindo, mezzo Kindra Scharich as an insanely determined suitor for Clorindo's love, and mezzo Nikola Printz as the title bored teenager who has been dragged to the provinces by her father to keep her safe from the sins of the city.

The entire cast was superb (from left to right): countertenor Justin Montigne as the overprotective father with a nasty streak; soprano Deborah Rosengaus as the noble Armidoro who is in love with Ermelinda and who has a vengeful streak himself; alto Sara Couden as Ermelinda's beloved who has followed her to the provinces in disguise; mezzo Nikola Printz as Ermelinda who convincingly transforms from a comic to a tragic character; the harpsichord continuo/conductor Jory Vinikour as himself; mezzo Kindra Scharich as Rosaura, who falls madly in love with Clorindo, who is in love with Ermelinda. This all sounds complicated but the clean staging by Ricci made it all clear. Elizabeth Flaherty in the robe was a charmingly bumbling supernumerary playing various roles with a switch of a costume moustache.

There were a few standouts in the cast for me. Sara Couden as Ormondo/Clorindo has a tall stature that makes her perfect for a trouser role. I have heard her in a few operas over the years with local companies, but this was the first time I fell in love with her gorgeous, bottomless alto voice. When things started looking dark, she sang a despairing aria translated as "What now?" which she sang so softly and emotively that it was genuinely heartbreaking. Mezzo Kindra Scharich as the rich, spoiled Rosaura was very funny in in her obsessive love scheming, and she also wore the most outrageous costume of the evening which she worked like a pro. She was also in great voice on the Saturday evening I attended.

Renaissance Italy is where opera was born in the late 17th century, and the style is very different from the long, langorous Baroque opera which followed. The arias are short, exquisite tunes that are not repeated and the recitatives sung over a combination of harpsichord and theorbo are snappy and expressive. The small orchestra, which was onstage in this production, felt very much part of the drama and they were as fun to watch as the vocal performers. Conductor/harpsichordist Jory Vinikour is a pretty big deal on the global Early Music scene, so his recent appointment as Ars Minerva's musical director is good news. He led a lively ensemble consisting of Cynthia Black, first violin; Laura Rubinstein-Salzedo, second violin; Aaron Westman, viola; Gretchen Claassen, cello; and the welcome return after a year's sabbatical of Adam Cockerham, theorbo.

The production was spare with elements of ornateness that worked well, highlighted by Matthew Nash's costumes and evocative, hand-drawn wall projections that effectively set each scene by Entropy, a young German artist. Céline Ricci directed the contrasting comic and tragic scenes well, and I only wish she would stage one of these operas in a real Venetian palace before they are all underwater. I'd buy an airplane ticket in a second.

The entire cast was superb (from left to right): countertenor Justin Montigne as the overprotective father with a nasty streak; soprano Deborah Rosengaus as the noble Armidoro who is in love with Ermelinda and who has a vengeful streak himself; alto Sara Couden as Ermelinda's beloved who has followed her to the provinces in disguise; mezzo Nikola Printz as Ermelinda who convincingly transforms from a comic to a tragic character; the harpsichord continuo/conductor Jory Vinikour as himself; mezzo Kindra Scharich as Rosaura, who falls madly in love with Clorindo, who is in love with Ermelinda. This all sounds complicated but the clean staging by Ricci made it all clear. Elizabeth Flaherty in the robe was a charmingly bumbling supernumerary playing various roles with a switch of a costume moustache.

There were a few standouts in the cast for me. Sara Couden as Ormondo/Clorindo has a tall stature that makes her perfect for a trouser role. I have heard her in a few operas over the years with local companies, but this was the first time I fell in love with her gorgeous, bottomless alto voice. When things started looking dark, she sang a despairing aria translated as "What now?" which she sang so softly and emotively that it was genuinely heartbreaking. Mezzo Kindra Scharich as the rich, spoiled Rosaura was very funny in in her obsessive love scheming, and she also wore the most outrageous costume of the evening which she worked like a pro. She was also in great voice on the Saturday evening I attended.

Renaissance Italy is where opera was born in the late 17th century, and the style is very different from the long, langorous Baroque opera which followed. The arias are short, exquisite tunes that are not repeated and the recitatives sung over a combination of harpsichord and theorbo are snappy and expressive. The small orchestra, which was onstage in this production, felt very much part of the drama and they were as fun to watch as the vocal performers. Conductor/harpsichordist Jory Vinikour is a pretty big deal on the global Early Music scene, so his recent appointment as Ars Minerva's musical director is good news. He led a lively ensemble consisting of Cynthia Black, first violin; Laura Rubinstein-Salzedo, second violin; Aaron Westman, viola; Gretchen Claassen, cello; and the welcome return after a year's sabbatical of Adam Cockerham, theorbo.

The production was spare with elements of ornateness that worked well, highlighted by Matthew Nash's costumes and evocative, hand-drawn wall projections that effectively set each scene by Entropy, a young German artist. Céline Ricci directed the contrasting comic and tragic scenes well, and I only wish she would stage one of these operas in a real Venetian palace before they are all underwater. I'd buy an airplane ticket in a second.

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

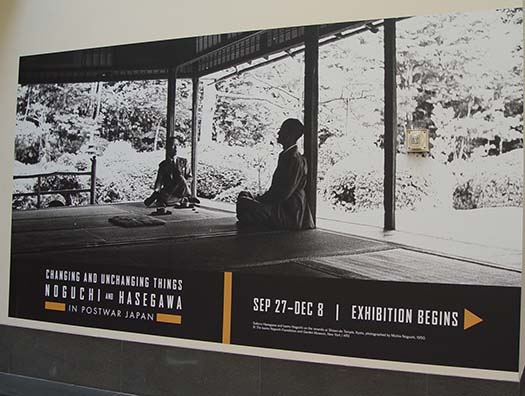

Noguchi and Hasegawa at the Asian Art Museum

There is a wonderful exhibit at the Asian Art Museum featuring the work of Isamu Noguchi (mostly sculpture) and Saboru Hasegawa (mostly woodblock prints).

Born in the first decade of the 20th century, they both had complicated, interesting artistic lives that fused traditional Asian forms with modern Western art. Both studied with artists in Paris during the early 1930s and both were locked up in internment camps during World War Two, Hasegawa in Japan for his pacifism and Noguchi in the United States for his ethnicity. According to an informative article by Tony Bravo about the exhibit in the SF Chronicle, "During Noguchi’s 1950 tour of Japan, Noguchi traveled to the country in an attempt to reconnect with his father’s Japanese family roots. Hasegawa, then working as a teacher, was fluent in English and became Noguchi’s tour guide...As the artists toured Buddhist sites and traditional gardens, and met traditional art makers in Japan, an exchange developed between them."

The friendship was deep and productive, and this exhibit focuses on work created by both of them during the seven years before Hasegawa's early death at age 50 of cancer in San Francisco, where he was teaching at the College of Arts and Crafts, a job he secured through the intervention of Noguchi and Alan Watts, author of The Way of Zen.

The exhibit feels a bit off-balance at first because Noguchi's sculptures dominate the two rooms...

...making Hasegawa's monochromatic prints feel somewhat like literal wallflowers.

On return visits to the show, it was the Hawegawa prints that stood out for me. Some of them looked like a Japanese woodblock version of Joan Miró, with spareness and complexity residing in the same frame.

Though it's a small exhibit, I am still discovering new details and what feels like completely new works with each visit.

It closes on Sunday, December 8th, so if you have a chance, do check it out in the next couple of weeks.

If you are in San Francisco for the holiday weekend, this Sunday, December 1st is a free admission day at the Asian Art Museum. Check it out and you can see my friend James Parr's favorite Noguchi sculpture above, the 1950 My Mu.

Born in the first decade of the 20th century, they both had complicated, interesting artistic lives that fused traditional Asian forms with modern Western art. Both studied with artists in Paris during the early 1930s and both were locked up in internment camps during World War Two, Hasegawa in Japan for his pacifism and Noguchi in the United States for his ethnicity. According to an informative article by Tony Bravo about the exhibit in the SF Chronicle, "During Noguchi’s 1950 tour of Japan, Noguchi traveled to the country in an attempt to reconnect with his father’s Japanese family roots. Hasegawa, then working as a teacher, was fluent in English and became Noguchi’s tour guide...As the artists toured Buddhist sites and traditional gardens, and met traditional art makers in Japan, an exchange developed between them."

The friendship was deep and productive, and this exhibit focuses on work created by both of them during the seven years before Hasegawa's early death at age 50 of cancer in San Francisco, where he was teaching at the College of Arts and Crafts, a job he secured through the intervention of Noguchi and Alan Watts, author of The Way of Zen.

The exhibit feels a bit off-balance at first because Noguchi's sculptures dominate the two rooms...

...making Hasegawa's monochromatic prints feel somewhat like literal wallflowers.

On return visits to the show, it was the Hawegawa prints that stood out for me. Some of them looked like a Japanese woodblock version of Joan Miró, with spareness and complexity residing in the same frame.

Though it's a small exhibit, I am still discovering new details and what feels like completely new works with each visit.

It closes on Sunday, December 8th, so if you have a chance, do check it out in the next couple of weeks.

If you are in San Francisco for the holiday weekend, this Sunday, December 1st is a free admission day at the Asian Art Museum. Check it out and you can see my friend James Parr's favorite Noguchi sculpture above, the 1950 My Mu.

Thursday, November 21, 2019

Hansel and Gretel at the SF Opera

Cannibalism. Serial Murder. Child abuse. Starvation. Sugar. Even by the the dark standards of Grimm's Children's and Household Tales, Hansel and Gretel has always struck me as especially brutal. Thomas Pynchon wrote a scatalological riff on the fairy tale in his novel, Gravity's Rainbow, and the Yugoslavian film director Dušan Makavejev used it as a subtext in his outrageous 1974 Sweet Movie. I've always been curious what the late 19th century German composer Englebert Humperdinck did with the tale in his popular opera, and finally got to see it for the first time at the San Francisco Opera last Sunday afternoon. (Sasha Cooke and Heidi Stober above as Hansel and Gretel, all photos by Cory Weaver.)

SF Opera produced Hansel and Gretel for three straight seasons, 1929-1932, and then waited 70 years to produce it again in 2002. I missed that production which was widely praised for its dark, surrealist spin, but 17 years later another British take has arrived at the War Memorial Opera House. First off, the opera itself turns out to be musically great, an intriguing mixture of German folk music and Wagnerian orchestral density.

Hansel and Gretel are written for two sopranos, and both Sasha Cooke and Heidi Strober were at the top of their performing game, sounding marvelous and looking convincing as outsized children trying to survive food deprivation, a hateful mother, and a scary haunted forest where a witch wanted to eat them after a good roasting in her oven.

The British production designer and director of this show, Antony McDonald, creates stunning visual moments but I questioned some of his staging decisions. When the two babes in the wood are being threatened in Act II, they are protected by 14 guardian angels during the most beautiful extended orchestral music of the opera. In this version, the guardians are Disneyfied fairy tale characters which was a little too cutesy and meta for its own good. I immediately thought of Rob Lowe and Snow White at the 1989 Academy Awards which took me out of the opera completely. One of the few positive mythologies I took from a quasi-Christian upbringing was the idea of Guardian Angels, and I felt very cheated not seeing them.

In the final act, Hansel and Gretel discover the witch's house which in this production is modeled after Hitchcock's Psycho house.

That would be fine, except that there is an extended dramatic sequence where the children are eating sugary treats that make up the house, but here it just looked like they were eating wood. It's not good to be this literal around fantasy, but a certain surreal consistency counts. That also goes for the death of the witch, which includes the satisfying physical detail of making her inspect something in the oven, then PUSHING HER IN. That doesn't happen in this production either.

None of this particularly matters, because the orchestra under Christopher Franklin sounds so exquisite, and the performers are all wonderful, including Robert Brubaker above as a non-binary witch, along with Alfred Walker as Father and Mary Evelyn Hangley stepping in at the last minute for an indisposed MIchaela Martens as the evil Mother. "Work or starve" is her Act ! injunction towards her children and it feels utterly resonant right now.

SF Opera produced Hansel and Gretel for three straight seasons, 1929-1932, and then waited 70 years to produce it again in 2002. I missed that production which was widely praised for its dark, surrealist spin, but 17 years later another British take has arrived at the War Memorial Opera House. First off, the opera itself turns out to be musically great, an intriguing mixture of German folk music and Wagnerian orchestral density.

Hansel and Gretel are written for two sopranos, and both Sasha Cooke and Heidi Strober were at the top of their performing game, sounding marvelous and looking convincing as outsized children trying to survive food deprivation, a hateful mother, and a scary haunted forest where a witch wanted to eat them after a good roasting in her oven.

The British production designer and director of this show, Antony McDonald, creates stunning visual moments but I questioned some of his staging decisions. When the two babes in the wood are being threatened in Act II, they are protected by 14 guardian angels during the most beautiful extended orchestral music of the opera. In this version, the guardians are Disneyfied fairy tale characters which was a little too cutesy and meta for its own good. I immediately thought of Rob Lowe and Snow White at the 1989 Academy Awards which took me out of the opera completely. One of the few positive mythologies I took from a quasi-Christian upbringing was the idea of Guardian Angels, and I felt very cheated not seeing them.

In the final act, Hansel and Gretel discover the witch's house which in this production is modeled after Hitchcock's Psycho house.

That would be fine, except that there is an extended dramatic sequence where the children are eating sugary treats that make up the house, but here it just looked like they were eating wood. It's not good to be this literal around fantasy, but a certain surreal consistency counts. That also goes for the death of the witch, which includes the satisfying physical detail of making her inspect something in the oven, then PUSHING HER IN. That doesn't happen in this production either.

None of this particularly matters, because the orchestra under Christopher Franklin sounds so exquisite, and the performers are all wonderful, including Robert Brubaker above as a non-binary witch, along with Alfred Walker as Father and Mary Evelyn Hangley stepping in at the last minute for an indisposed MIchaela Martens as the evil Mother. "Work or starve" is her Act ! injunction towards her children and it feels utterly resonant right now.