Last weekend's San Francisco Symphony concerts were marketed as "cinematic inspirations" which turned out not to be the case at all. Although Shostakovich, Walton, and Prokofiev all composed memorable film scores during their careers, the only one that was cinematic was a 1938 Shostakovich Funeral March for the 1938 Soviet movie The Great Citizen, heavily edited by Stalin himself. It would have been interesting to have the actual film clip showing with the 8-minute piece but that didn't happen. Shostakovich's musical skill was evident in the performance but it did seem odd to start a concert off with a funeral march.

This was followed by the British composer William Walton's 1928 Viola Concerto which was a delightful surprise. Walton (1902-1983) is best known now for his film scores to Olivier's cinematic Shakespeare adaptations (Henry V, Richard III, and Hamlet) but during the 1920's he was considered a promising modernist with Facade, his success de scandale with Edith Sitwell on a megaphone, the over-the-top oratorio Belshazzar's Feast, and this viola concerto which was premiered by the violist and composer Paul Hindemith. Walton's subsequent career was less successful, with critical consensus proclaiming him dull and old-fashioned for the next 40 years. (All production photos are by Stefan Cohen.)

In any case, this early viola concerto is lively and piquant from beginning to end, and SF Symphony principal violist Jonathan Vinocour gave an exquisite performance. Vinocour still looks like the handsome, slightly nerdy chemistry major that he once was, and he's been one of my favorite musicians in the orchestra since his arrival in 2009. His solo moments during full orchestral concerts are always a highlight for their tonal beauty and exceptional musicianship, and it was a real treat to hear him as a concerto soloist.

Sergei Prokofiev also composed memorable scores for films like Alexander Nevsky, Ivan the Terrible, and Lieutenant Kijé, but his 1928 Symphony No. 3 has nothing to do with film but is a reworking of the final act of his unproduced opera The Fiery Angel. Spanish guest conductor Gustavo Gimeno did a fine job with the entire concert, but the Prokofiev symphony did not fare so well.

The opera itself wasn't produced until 1955 in Italy, and didn't appear until the 1990s in Russia, where a famous production directed by David Freeman toured the world, eventually appearing at the San Francisco Opera. (You can actually see a filmed version of the St. Petersburg production on YouTube, click here.) The story itself is based on a satirical Russian symbolist novel and in this operatic adaptation it's totally bonkers. It is in five short acts, culminating in an insane final act set in a medieval convent filled with nuns possessed by demons confronting the Grand Inquisitor. It's like the Ken Russell film The Devils, except with great music.

The problem with the symphony is it starts at full voltage and from there really has nowhere to go, unlike the opera which is essentially a chamber piece until the 50+ nuns appear for the insane finale. In other words, the four-movement symphony just sounded very loud and incoherent, and made me want to hear the opera instead, either in concert or on the stage.

Tuesday, April 30, 2024

Thursday, April 25, 2024

Mark Morris Choreographs the Deaths of Socrates and Jesus

The Mark Morris Dance Group brought a pair of serious, austere ballets to UC Berkeley's Cal Performances last weekend. It started with Socrates, first presented in 2010, which is set to a three-movement, 35-minute work by Erik Satie from 1918 about the the Greek philosopher. I have long read about this 1918 composition which is usually described as "unclassifiable," but had never heard it before.

The chamber work for piano or small ensemble and voice(s) was originally commissioned by the Singer sewing machine heiress Princesse de Polignac, a fabulous lesbian living in Paris who hosted a music salon. Besides Satie, she commissioned and premiered works by local composers such as Fauré, Debussy, Poulenc, Ravel, and Stravinsky. (Click here for a quick, fun bio). The musical version of Socrate used by Morris is for piano and solo vocalist, which was performed exquisitely last Friday by tenor Brian Giebler with accompaniment by Colin Fowler. The text is a French translation of excerpts from Plato's Symposium, Phaedrus and Phaedo, culminating in a description of Socrates's state-enforced suicide via hemlock.

The choreography alternates between abstract representations of moods and more literal representations of various actions, all of it matching the coolness and lack of emotionality in the music. The effect was gorgeous, and the movement intertwined with the spare music so well that I can't imagine listening to it without picturing these dancers, particularly Billy Smith (above, with the orange skirt). A longtime member of the company since 2010, Smith would repeatedly make a magical transformation from free-flowing limbs to exact stillness, in the pose of a Greek frieze, and have it look casual.

The second half of the program was the world premiere of Via Dolorosa, a 40-minute dance depicting the fourteen Stations of the Cross. The piece began with a 2022 commission from harpist Peter Ramsay to composer Nico Muhly for a solo harp piece and the American-British poet Alice Goodman provided poems for each step of the Christian ritual depicting the journey to Christ's crucifixion.

Morris liked Muhly's music and choreographed a dance that felt very similar in affect and style to Socrates. He jettisoned Goodman's strong, pithy poems to the program book, which was probably a good idea to keep the staging simple. In the pit was solo harpist Parker Ramsay, the original commissioner.

In his wildly candid 2019 memoir, Morris wrote: "I have always been a big admirer of religion: the swindle of religion. I love the snake oil, healings, and miracles...It doesn't matter if you believe in it -- I don't believe in any of it -- but it happens. It's a fact. And it's powerful. Prayer (or "mindfulness") may not hurt, even though it's a waste of time. But I don't argue with any of it. I love magic. I love a sunset. I love a baby. I love the ideas and myths of religion, its trappings, though what I really love is the kindness of people who are devoutly religious and don't proselytize."

I feel the same way about religion, though I have to confess to a complete antipathy to the Passion narrative of the events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus. I have always found the story repulsive and its fetishization sort of creepy, such as in Mel Gibson's ultraviolent The Passion of Christ. I also dislike the story in Mark Adamo's opera The Gospel According to Mary and John Adams's oratorio The Gospel According to the Other Mary, in the old Hollywood Technicolor spectacles such as King of Kings and The Greatest Story Ever Told, along with the rock musical Jesus Christ Superstar and the Pasolini art film The Gospel According to Matthew.

Passion objections aside, the dancing and the choreography was exquisite and had a beauty quite apart from the narrative. Nico Muhly's music managed to make 40 minutes of solo harp interesting which is an achievement in itself, and the lighting design by Nicole Pearce on Howard Hodgkin's backdrop was masterful. My only complaint was with Elizabeth Kurtzman's sackcloth-looking costumes which flattered no one.

There was a very loud boo from an audience member at the end of the show, which I found amusing. Almost as a response, the rest of the audience quickly rose for the requisite standing ovation. (Pictured above in front of the ensemble are composer Nico Muhly, choreographer Mark Morris, lighting designer Nicole Pearce, and costume designer Elizabeth Kurtzman.)

The chamber work for piano or small ensemble and voice(s) was originally commissioned by the Singer sewing machine heiress Princesse de Polignac, a fabulous lesbian living in Paris who hosted a music salon. Besides Satie, she commissioned and premiered works by local composers such as Fauré, Debussy, Poulenc, Ravel, and Stravinsky. (Click here for a quick, fun bio). The musical version of Socrate used by Morris is for piano and solo vocalist, which was performed exquisitely last Friday by tenor Brian Giebler with accompaniment by Colin Fowler. The text is a French translation of excerpts from Plato's Symposium, Phaedrus and Phaedo, culminating in a description of Socrates's state-enforced suicide via hemlock.

The choreography alternates between abstract representations of moods and more literal representations of various actions, all of it matching the coolness and lack of emotionality in the music. The effect was gorgeous, and the movement intertwined with the spare music so well that I can't imagine listening to it without picturing these dancers, particularly Billy Smith (above, with the orange skirt). A longtime member of the company since 2010, Smith would repeatedly make a magical transformation from free-flowing limbs to exact stillness, in the pose of a Greek frieze, and have it look casual.

The second half of the program was the world premiere of Via Dolorosa, a 40-minute dance depicting the fourteen Stations of the Cross. The piece began with a 2022 commission from harpist Peter Ramsay to composer Nico Muhly for a solo harp piece and the American-British poet Alice Goodman provided poems for each step of the Christian ritual depicting the journey to Christ's crucifixion.

Morris liked Muhly's music and choreographed a dance that felt very similar in affect and style to Socrates. He jettisoned Goodman's strong, pithy poems to the program book, which was probably a good idea to keep the staging simple. In the pit was solo harpist Parker Ramsay, the original commissioner.

In his wildly candid 2019 memoir, Morris wrote: "I have always been a big admirer of religion: the swindle of religion. I love the snake oil, healings, and miracles...It doesn't matter if you believe in it -- I don't believe in any of it -- but it happens. It's a fact. And it's powerful. Prayer (or "mindfulness") may not hurt, even though it's a waste of time. But I don't argue with any of it. I love magic. I love a sunset. I love a baby. I love the ideas and myths of religion, its trappings, though what I really love is the kindness of people who are devoutly religious and don't proselytize."

I feel the same way about religion, though I have to confess to a complete antipathy to the Passion narrative of the events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus. I have always found the story repulsive and its fetishization sort of creepy, such as in Mel Gibson's ultraviolent The Passion of Christ. I also dislike the story in Mark Adamo's opera The Gospel According to Mary and John Adams's oratorio The Gospel According to the Other Mary, in the old Hollywood Technicolor spectacles such as King of Kings and The Greatest Story Ever Told, along with the rock musical Jesus Christ Superstar and the Pasolini art film The Gospel According to Matthew.

Passion objections aside, the dancing and the choreography was exquisite and had a beauty quite apart from the narrative. Nico Muhly's music managed to make 40 minutes of solo harp interesting which is an achievement in itself, and the lighting design by Nicole Pearce on Howard Hodgkin's backdrop was masterful. My only complaint was with Elizabeth Kurtzman's sackcloth-looking costumes which flattered no one.

There was a very loud boo from an audience member at the end of the show, which I found amusing. Almost as a response, the rest of the audience quickly rose for the requisite standing ovation. (Pictured above in front of the ensemble are composer Nico Muhly, choreographer Mark Morris, lighting designer Nicole Pearce, and costume designer Elizabeth Kurtzman.)

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

2024 SF Silent Film Festival

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival unspooled 20+ films last week at the Palace of Fine Arts. The festival's usual home, the Castro Theatre, is currently being destroyed as a movie palace by Another Planet Entertainment while they repurpose that building for a concert venue.

The huge hall surrounding the Palace of Fine Arts has been used over the decades for everything from Parks storage to tennis courts to a telephone book distribution center. The theater was added to the structure in 1970.

Of all the arts, movies are the most direct at transporting a viewer through time, and silent films doubly so. This makes the experience of watching old-time movies in a theater with an audience and live musicians feel paradoxically modern. !00+ years ago, movies were in their infancy, and audiences were not able to go back in time via cinema. We are in a new historical moment.

On Thursday the day began with a series of lectures and clips in a popular annual program called Amazing Tales from the Archives. A dry, witty Bryony Dixon, silent film curator at the British Film Institute, introduced a series of clips from travel shorts of the 1920s called Travelaughs that featured the young Michael Powell, future director, as a goofball nature lover. This was followed by the academic Denise Khor, above, introducing the 1914 The Oath of the Sword, a 30-minute variant on Madame Butterfly made by an all Japanese-American cast and production company.

All the clips were accompanied by Stephen Horne, my favorite silent film composer/improviser. He plays piano with the occasional additions of a flute or accordion, and he somehow manages to inhabit the interior of characters in a penetrating, often melancholic fashion.

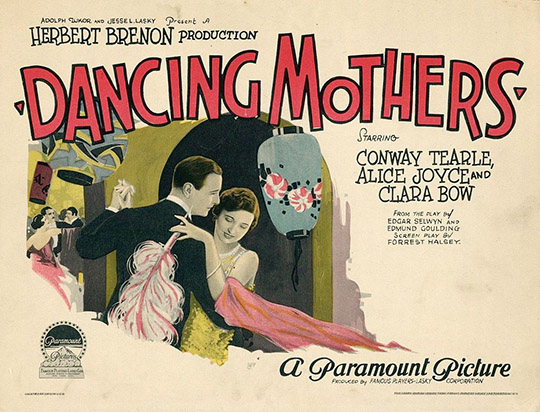

The afternoon movie was a Clara Bow double-bill, starting with a 1923 short called The Pill Pounder. Thought to be forever lost, a partial print was recently discovered at a film distribution parking lot sale in Omaha, Nebraska. The feature was the 1926 Dancing Mothers, which was a direct hit of time travel to the Prohibition Jazz Age era among New York socialites. The melodramatic plot surprisingly resolved as a riff on A Doll's House, except drenched in sex, cigarettes, and booze.

The Palace of Fine Arts is a slog to get to via public transportation, but there are compensations, such as a series of young women dressed in fabulous outfits posing all over the Palace on a cold, rainy Saturday night.

That's when we returned to see a Buster Keaton double bill accompanied by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

The main feature was the 1934 Sherlock, Jr., but the real revelation, and the funnier film, was the 1920 short One Week. When the grotesque, assemble-it-yourself home starts rotating during a storm, it's one of the most inspired Keaton sequences ever.

I could only go out twice because I had to mostly stay in bed last week for boring reasons, but was able to read the 120-page program which is an unusually beautiful and brilliant collection of essays and photos by writers and historians from around the world.

The huge hall surrounding the Palace of Fine Arts has been used over the decades for everything from Parks storage to tennis courts to a telephone book distribution center. The theater was added to the structure in 1970.

Of all the arts, movies are the most direct at transporting a viewer through time, and silent films doubly so. This makes the experience of watching old-time movies in a theater with an audience and live musicians feel paradoxically modern. !00+ years ago, movies were in their infancy, and audiences were not able to go back in time via cinema. We are in a new historical moment.

On Thursday the day began with a series of lectures and clips in a popular annual program called Amazing Tales from the Archives. A dry, witty Bryony Dixon, silent film curator at the British Film Institute, introduced a series of clips from travel shorts of the 1920s called Travelaughs that featured the young Michael Powell, future director, as a goofball nature lover. This was followed by the academic Denise Khor, above, introducing the 1914 The Oath of the Sword, a 30-minute variant on Madame Butterfly made by an all Japanese-American cast and production company.

All the clips were accompanied by Stephen Horne, my favorite silent film composer/improviser. He plays piano with the occasional additions of a flute or accordion, and he somehow manages to inhabit the interior of characters in a penetrating, often melancholic fashion.

The afternoon movie was a Clara Bow double-bill, starting with a 1923 short called The Pill Pounder. Thought to be forever lost, a partial print was recently discovered at a film distribution parking lot sale in Omaha, Nebraska. The feature was the 1926 Dancing Mothers, which was a direct hit of time travel to the Prohibition Jazz Age era among New York socialites. The melodramatic plot surprisingly resolved as a riff on A Doll's House, except drenched in sex, cigarettes, and booze.

The Palace of Fine Arts is a slog to get to via public transportation, but there are compensations, such as a series of young women dressed in fabulous outfits posing all over the Palace on a cold, rainy Saturday night.

That's when we returned to see a Buster Keaton double bill accompanied by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

The main feature was the 1934 Sherlock, Jr., but the real revelation, and the funnier film, was the 1920 short One Week. When the grotesque, assemble-it-yourself home starts rotating during a storm, it's one of the most inspired Keaton sequences ever.

I could only go out twice because I had to mostly stay in bed last week for boring reasons, but was able to read the 120-page program which is an unusually beautiful and brilliant collection of essays and photos by writers and historians from around the world.

Thursday, April 04, 2024

Irving Penn Retrospective at the deYoung

A huge retrospective of the work of photographer Irving Penn (1917-2009) has opened at the deYoung Museum in Golden Gate Park, and will stay there through July.

Penn's career took off under the mentorship of Alexander Liberman, the art director of Vogue magazine from 1941 to 1962, where Penn was hired as an associate graphic artist until Liberman suggested he try photography.

After a stint with the American Field Service in Europe during World War Two, he returned to New York where he captured cultural celebrities and fashion models for Vogue. Pictured is the 1948 Ballet Society, featuring George Balanchine, Corrado Cagli, Tanaquil Le Clercq, and Vittorio Rieti.

The magazine sent Penn to France for the Paris Haute Couture Week but he didn't care for the mad jockeying involved in the live runway shows, so he arranged for an empty attic studio with great light to photograph the clothing on his own models. Pictured is Balenciaga Mantle Coat (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), Paris, 1950.

One of those models was the Swedish Lisa Fonssagrives, who Penn married in 1950. She is pictured above in Woman with Roses (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in Lafaurie Dress), Paris, 1950.

He also played around with a series of abstract female nudes that look like photographic attempts at Henry Moore sculptures, but they don't quite work. Pictured is Nude No. 18, New York, 1949-1950.

In 1948 he want on assignment to Cuzco, Peru, where he rented the local photographer's studio and took portraits of Indian peasants with the same gray/white backgrounds as his fashion models. Pictured is Cuzco Children. This was the first of a series of ethnographic photo essays he created over the decades that haven't aged well. The formal distancing of exotic others comes off as slightly grotesque.

In this exhibit, there is an amusing selection of San Francisco Hippie photos from 1967, which Penn did on assignment from Look magazine, including Hell's Angel (Doug), San Francisco.

His true genius lay in creating iconographic images of cultural artists, such as the young Audrey Hepburn, Paris, 1951...

...and the old Colette, Paris, 1951...

...and a dappter Jean Cocteau, Paris, 1948.

He continued working over the decades with his own advertising studio, while continuing to capture artists, such as a zaftig Alvin Ailey, New York, 1971...

...and the quartet pictured above: Issey Miyake, New York, 1988; Richard Avedon, New York, 1978; S.J. Perelman, New York, 1962; and Gianni Versace, New York, 1987.

Penn's career took off under the mentorship of Alexander Liberman, the art director of Vogue magazine from 1941 to 1962, where Penn was hired as an associate graphic artist until Liberman suggested he try photography.

After a stint with the American Field Service in Europe during World War Two, he returned to New York where he captured cultural celebrities and fashion models for Vogue. Pictured is the 1948 Ballet Society, featuring George Balanchine, Corrado Cagli, Tanaquil Le Clercq, and Vittorio Rieti.

The magazine sent Penn to France for the Paris Haute Couture Week but he didn't care for the mad jockeying involved in the live runway shows, so he arranged for an empty attic studio with great light to photograph the clothing on his own models. Pictured is Balenciaga Mantle Coat (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), Paris, 1950.

One of those models was the Swedish Lisa Fonssagrives, who Penn married in 1950. She is pictured above in Woman with Roses (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in Lafaurie Dress), Paris, 1950.

He also played around with a series of abstract female nudes that look like photographic attempts at Henry Moore sculptures, but they don't quite work. Pictured is Nude No. 18, New York, 1949-1950.

In 1948 he want on assignment to Cuzco, Peru, where he rented the local photographer's studio and took portraits of Indian peasants with the same gray/white backgrounds as his fashion models. Pictured is Cuzco Children. This was the first of a series of ethnographic photo essays he created over the decades that haven't aged well. The formal distancing of exotic others comes off as slightly grotesque.

In this exhibit, there is an amusing selection of San Francisco Hippie photos from 1967, which Penn did on assignment from Look magazine, including Hell's Angel (Doug), San Francisco.

His true genius lay in creating iconographic images of cultural artists, such as the young Audrey Hepburn, Paris, 1951...

...and the old Colette, Paris, 1951...

...and a dappter Jean Cocteau, Paris, 1948.

He continued working over the decades with his own advertising studio, while continuing to capture artists, such as a zaftig Alvin Ailey, New York, 1971...

...and the quartet pictured above: Issey Miyake, New York, 1988; Richard Avedon, New York, 1978; S.J. Perelman, New York, 1962; and Gianni Versace, New York, 1987.