Whenever visiting the Palace of the Legion of Honor Museum, I usually want to escape outside to the stunning beauty of Lincoln Park Municipal Golf Course which surrounds it. However, I'm still breaking in a new hip so I happily roamed the museum instead last Saturday for the opening of a new fashion exhibit by a Chinese coturier named Guo Pei.

While local socialite Dede Wilsey has been in charge of the Fine Arts Museums for the last few decades, there have been lots of jewelry and fashion exhibits which seems to be her thing. A few of the shows have been fabulous (the Jean-Paul Gaultier exhibit from Montreal at the deYoung, for instance) and quite a few have been sad embarrassments (the recent "Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love" at the deYoung being a prime example). So it's a joy to report that the Guo Pei exhibit is one of the most astonishing museum installations I have ever seen.

Guo Pei is a 53-year-old Beijing-based fashion designer who was "invited to be a member of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, the chief governing body of the high-fashion industry, allowing her to show on the Paris Haute Couture Week calendar," according to her website.

The downstairs special exhibit is filled with amazing examples of her work from the last 20 years, but the physical space is crowded and a bit claustrophobic, not allowing the work to breathe properly.

However, somebody had the bright idea to install most of the showstoppers in the permanent galleries upstairs, and the proximity of the sculpturally magnificent outfits with the art surrounding them elevate both.

The detailing in these outfits is staggering, and her more elaborate creations require two years and 4,000 hours of labor from her 500-employee design studio, not to mention at least a medium-sized fortune to purchase.

In an interview with L'Officiel in Singapore, Guo Pei says: "I love couture art, as couture can have a longer, even permanent life. Unlike ready-to-wear, which could be very popular at a time, but be forgotten at another. I hope my couture can be like the museum pieces stored in galleries or museums, being inherited. Because true haute couture can be appreciated through time, for years, they become a glance of past time, where they can restore past glory and resplendence."

This is Guo Pei's first museum exhibit, so it looks like somebody's dreams have come true.

Many of these pieces don't look like they could actually be worn by normal humans, but their mixture of craft and sculptural experimentation put them into a different realm of art.

Some of the installations are witty and destabilizing.

The absurdly ornate French antiques rooms look much more interesting with exquisitely dressed mannequins inhabiting them.

And the erotics of antique French bedroom sets has never been so obvious.

Tuesday, April 26, 2022

Tuesday, April 19, 2022

Alice Neel Retrospective at the de Young

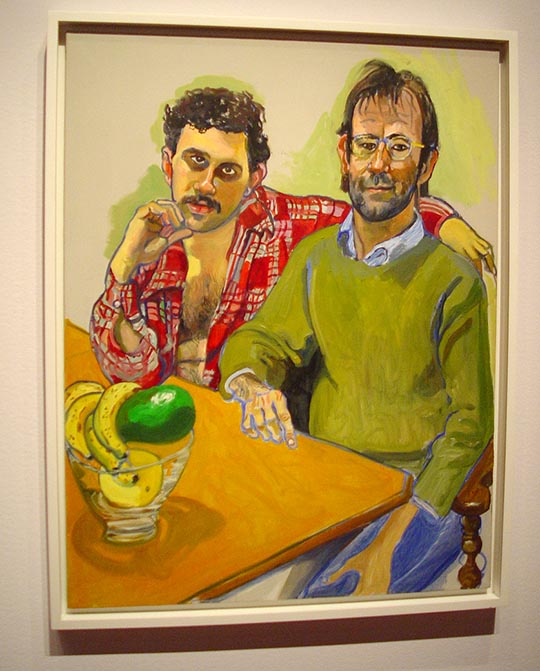

When SFMOMA reopened in 2016 after its huge expansion, I saw the painting above for the first time, and it stopped me dead in my tracks. The casual yet penetrating depiction of a gay couple (Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, 1978) sitting at a kitchen table while staring back at the viewer, was unlike anything else in the museum. The artist, Alice Neel, was completely unknown to me, but I instantly became a member of her admiring cult.

Alice Neel (1900-1984) was desperately poor and unappreciated artistically most of her life for a number of reasons: her gender, her figurative style when abstraction was the fashion, her domicile in New York's Spanish Harlem when the art scene was centered in Greenwich Village, and her sincere far-left politics bred during the 1930s Depression. She was also, like most great painters, an egomaniac who had her own vision. In 1974, she was finally given a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and spent her last decade as a minor celebrity, even appearing on the Johnny Carson show a couple of times. The power of her work, however, is finally being recognized at the highest institutional level, with a major show last year at the Metropolitan Museum in New York which has now traveled to the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

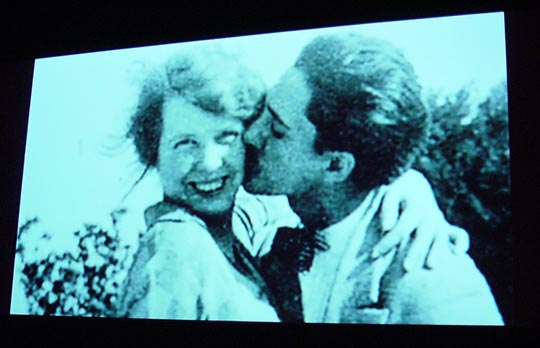

A couple of weekends ago, Andrew Neel brought his 2007 documentary about his grandmother, Alice Neel, to the deYoung Museum, and it was a fascinating work of art on its own. (You can watch it on Amazon Prime, which is highly recommended if you are planning on seeing the exhibit.) Alice was from a working-class Pennsylvania family who went to a Women's Art School in Philadelphia. At a summer school, she met the upper-class Cuban art student Carlos Enriquez, married him and had a daughter. This did not thrill Enriquez's Cuban family. While the couple were trying to make their way as starving artists in 1920s New York, their daughter died of diphtheria. When another daughter, Isabetta, was born, Carlos took her to Cuba and left the child with his parents while he took off for Paris. (The painting above is the 1926 portrait, Carlos Enriquez.)

The abandoned Alice went into a suicidal, clinical depression. After a few unsuccessful suicide attempts, and a year in a Philadelphia mental institution, Alice decided that "I could jump out a window or just serve my time," and she decided to live. That included hooking up with a young Puerto Rican musician, who is in the 1936 portrait, Jose Santiago Negron.

In 1939, she had a son by him, Richard, and a couple of years later Hartley was born during her union with the Communist documentary filmmaker Sam Brody. The painting above is Hartley and Richard, 1950.

The two important things parents can do for their children are to give them love and to make them feel safe. From the accounts in Andrew's very frank family documentary, there was plenty of the former but not much of the latter, with Richard getting the worst of it via constant bullying from Sam Brody. Richard is pictured above in a 1963 portrait.

It's not particularly surprising that Richard rebelled at the Bohemian world he had grown up in and became a Nixon-loving corporate lawyer for Pan Am. Alice was not amused, and painted the rather cruel portrait above, Richard in the Era of the Corporation (1978-79).

Hartley, shown above in a 1966 portrait, became a radiologist.

Alice's bohemianism extended to her frankness about nudity and sex, in pictures that are still shocking, like the 1935 Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom).

Her portrait of the art critic John Perreault is both erotic and funny. In an essay on the painter Joan Mitchell, Perreault writes: "“Her Fifth Sin,” he wrote of Mitchell, “was that she didn’t have a wife to promote her and steady the helm. Wild woman Alice Neel once told me, when I was posing naked for her, that she would have been famous much sooner if, like Jackson Pollock, she had had Lee Krasner for a wife, or like de Kooning she had had an Elaine.”

Neel's series of portraits of pregnant women are unlike any other before or since, without a hint of sentimentality. (Above is the 1964 Pregnant Maria)

Alice had problems with the feminist movement, noting that it was mostly run by white bourgie women, but the movement benefited her immensely at the end of her life. Pictured above is the echt-1972 Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), with its still slightly shocking tuft of armpit hair confronting the viewer.

Alice painted portraits of every type of person imaginable: the rich, poor, famous, nobodies, family, and strangers. In 1971, she invited the San Francisco concert pianist Robert Avedis Hagopian (1945-1984) to her home studio and painted the portrait above. He was one of the many eventual AIDS casualties that figure among her sitters, including the Detroit-born artist Brian Buczak who is in the first photo of this post. Alice kept this painting until her own death, which was then bought by the Hagopian family, and which is now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

She only painted one self-portrait, and waited until the age of 80 where she casually, defiantly, and subversively lets it all hang out. She looks like an old Irish grandmother who is somehow stronger than anybody else in the world.

Alice Neel (1900-1984) was desperately poor and unappreciated artistically most of her life for a number of reasons: her gender, her figurative style when abstraction was the fashion, her domicile in New York's Spanish Harlem when the art scene was centered in Greenwich Village, and her sincere far-left politics bred during the 1930s Depression. She was also, like most great painters, an egomaniac who had her own vision. In 1974, she was finally given a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and spent her last decade as a minor celebrity, even appearing on the Johnny Carson show a couple of times. The power of her work, however, is finally being recognized at the highest institutional level, with a major show last year at the Metropolitan Museum in New York which has now traveled to the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

A couple of weekends ago, Andrew Neel brought his 2007 documentary about his grandmother, Alice Neel, to the deYoung Museum, and it was a fascinating work of art on its own. (You can watch it on Amazon Prime, which is highly recommended if you are planning on seeing the exhibit.) Alice was from a working-class Pennsylvania family who went to a Women's Art School in Philadelphia. At a summer school, she met the upper-class Cuban art student Carlos Enriquez, married him and had a daughter. This did not thrill Enriquez's Cuban family. While the couple were trying to make their way as starving artists in 1920s New York, their daughter died of diphtheria. When another daughter, Isabetta, was born, Carlos took her to Cuba and left the child with his parents while he took off for Paris. (The painting above is the 1926 portrait, Carlos Enriquez.)

The abandoned Alice went into a suicidal, clinical depression. After a few unsuccessful suicide attempts, and a year in a Philadelphia mental institution, Alice decided that "I could jump out a window or just serve my time," and she decided to live. That included hooking up with a young Puerto Rican musician, who is in the 1936 portrait, Jose Santiago Negron.

In 1939, she had a son by him, Richard, and a couple of years later Hartley was born during her union with the Communist documentary filmmaker Sam Brody. The painting above is Hartley and Richard, 1950.

The two important things parents can do for their children are to give them love and to make them feel safe. From the accounts in Andrew's very frank family documentary, there was plenty of the former but not much of the latter, with Richard getting the worst of it via constant bullying from Sam Brody. Richard is pictured above in a 1963 portrait.

It's not particularly surprising that Richard rebelled at the Bohemian world he had grown up in and became a Nixon-loving corporate lawyer for Pan Am. Alice was not amused, and painted the rather cruel portrait above, Richard in the Era of the Corporation (1978-79).

Hartley, shown above in a 1966 portrait, became a radiologist.

Alice's bohemianism extended to her frankness about nudity and sex, in pictures that are still shocking, like the 1935 Untitled (Alice Neel and John Rothschild in the Bathroom).

Her portrait of the art critic John Perreault is both erotic and funny. In an essay on the painter Joan Mitchell, Perreault writes: "“Her Fifth Sin,” he wrote of Mitchell, “was that she didn’t have a wife to promote her and steady the helm. Wild woman Alice Neel once told me, when I was posing naked for her, that she would have been famous much sooner if, like Jackson Pollock, she had had Lee Krasner for a wife, or like de Kooning she had had an Elaine.”

Neel's series of portraits of pregnant women are unlike any other before or since, without a hint of sentimentality. (Above is the 1964 Pregnant Maria)

Alice had problems with the feminist movement, noting that it was mostly run by white bourgie women, but the movement benefited her immensely at the end of her life. Pictured above is the echt-1972 Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), with its still slightly shocking tuft of armpit hair confronting the viewer.

Alice painted portraits of every type of person imaginable: the rich, poor, famous, nobodies, family, and strangers. In 1971, she invited the San Francisco concert pianist Robert Avedis Hagopian (1945-1984) to her home studio and painted the portrait above. He was one of the many eventual AIDS casualties that figure among her sitters, including the Detroit-born artist Brian Buczak who is in the first photo of this post. Alice kept this painting until her own death, which was then bought by the Hagopian family, and which is now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

She only painted one self-portrait, and waited until the age of 80 where she casually, defiantly, and subversively lets it all hang out. She looks like an old Irish grandmother who is somehow stronger than anybody else in the world.

Tuesday, April 12, 2022

Corigliano Triathalon at the SF Symphony

Last week the San Francisco Symphony offered the world premiere of a saxophone concerto by the famous 84-year-old American composer John Corigliano. The composer gave a charming introduction to the work from the stage, explaining that the piece was called Triathalon, Concerto for Saxophonist and Orchestra because each of the three movements used a different kind of instrument. The first movement, Leaps, featured a soprano saxophone; the middle movement, Lines, an alto saxophone; and the final Licks movement a baritone saxophone, with a hasty, circular return to the soprano sax at the end.

I have never warmed up to any of Corigliano's music over the decades, from his The Ghosts of Versailles opera to his AIDS-reflective Symphony #1 to his film soundtracks for Altered States and The Red Violin. Joshua Kosman in the SF Chronicle wrote a rave review of the new concerto (click here), so I was hoping this might be a conversion moment, but it was not. The soloist for whom it was written, Tim McAllister, was as virtuosic and entertaining as could be, but the music sounded banal and the integration between soloist and orchestra under debuting guest conductor Giancarlo Guerrero felt lacking, with the orchestra often just imitating the Leaps of the soprano sax, meandering during the melodic Lines, and motoring along for the timid Licks of the finale.

Still, it is always exciting to hear the San Francisco Symphony in new music, where they excel, and it was a joy seeing Wyatt Underhill in the Concertmaster's chair bumping elbows with Tim McAllister at the end of the performance.

Guest conductor Giancarlo Guerrero, originally from Central America, is the Music Director of the Nashville Symphony, and he brought along works that had never been performed here before. The other three pieces were all musical depictions of places: Adolphus Hailstork's 1985 An American Port of Call about Norfolk, Virginia; Antonio Estevez's 1942 Mediodia en el Lanno about the grassy prairies in central Venezuela; and finally Astor Piazzolla's 1952 Sinfonia Buenos Aires. Hailstork's depiction of Norfolk sounded like one fanfare after another without much evocation of water or boats and Guerrero played it too emphatically loud. The same was true for Piazzola's one attempt at a major symphonic work before he settled into his genius melding of classical music language and tango orchestra. The only work that was quieter and sheerly enjoyable was Estevez's 10-minute evocation of Venezuela's highlands.

I have never warmed up to any of Corigliano's music over the decades, from his The Ghosts of Versailles opera to his AIDS-reflective Symphony #1 to his film soundtracks for Altered States and The Red Violin. Joshua Kosman in the SF Chronicle wrote a rave review of the new concerto (click here), so I was hoping this might be a conversion moment, but it was not. The soloist for whom it was written, Tim McAllister, was as virtuosic and entertaining as could be, but the music sounded banal and the integration between soloist and orchestra under debuting guest conductor Giancarlo Guerrero felt lacking, with the orchestra often just imitating the Leaps of the soprano sax, meandering during the melodic Lines, and motoring along for the timid Licks of the finale.

Still, it is always exciting to hear the San Francisco Symphony in new music, where they excel, and it was a joy seeing Wyatt Underhill in the Concertmaster's chair bumping elbows with Tim McAllister at the end of the performance.

Guest conductor Giancarlo Guerrero, originally from Central America, is the Music Director of the Nashville Symphony, and he brought along works that had never been performed here before. The other three pieces were all musical depictions of places: Adolphus Hailstork's 1985 An American Port of Call about Norfolk, Virginia; Antonio Estevez's 1942 Mediodia en el Lanno about the grassy prairies in central Venezuela; and finally Astor Piazzolla's 1952 Sinfonia Buenos Aires. Hailstork's depiction of Norfolk sounded like one fanfare after another without much evocation of water or boats and Guerrero played it too emphatically loud. The same was true for Piazzola's one attempt at a major symphonic work before he settled into his genius melding of classical music language and tango orchestra. The only work that was quieter and sheerly enjoyable was Estevez's 10-minute evocation of Venezuela's highlands.

Friday, April 08, 2022

A Rousing Evening at the San Francisco Ballet

The San Francisco Ballet's Program 6, a mixed bill of three short works, opened on Wednesday and plays through next Tuesday. If you have the time and the money, check it out because the program is thoroughly entertaining. The opener was Prism, choreographed in 2000 by departing Artistic Director Helgi Tomasson to Beethoven's Piano Concerto #1. The highlight for me was the lovely orchestral performance by the Ballet Orchestra under conductor Martin West and especially the sensitive piano playing by long-time SF Ballet piano soloist Roy Bogas, who is retiring from the company after these performances.

The neo-Balanchine ballet's other highlight was the partnering of longtime principal dancers Yuan Yuan Tan, who premiered the role in San Francisco over 20 years ago, and Tiit Helmets. (All production photos are by Erik Tomasson.)

The second work was Finale Finale, a world premiere ballet by my favorite current choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, who has been nurtured by Tomasson with commissions in San Francisco for the last two decades. It is a gorgeously loose, complex, and funny piece set to Darius Milhaud's 1920 Le Boeuf sur le toit (literally The Ox on the Roof) which started out as a score for a Chaplin silent short and ended up as a ballet with a scenario by Cocteau. Milhaud had just spent two years working as a diplomatic secretary in Brazil, and the music is filled with danceable Latin tunes that dissolve into astringent fogs before bouncing back again. The orchestra gave a wonderful performance and the choreography was delightfully ambiguous, sometimes in lockstep with the music and other times doing its own thing altogether.

The ballet was created for seven dancers, including Dores Andre and Joseph Walsh (above), Isabella Devivo and Benjamin Freemantle, and the amusing trio of Elizabeth Powell, Cavan Conley, and Esteban Hernandez. They were all superb and seemed to be enjoying themselves immensely. The ballet is an instant classic.

The third work for a huge company contingent was The Promised Land, another world premiere by choreographer Dwight Rhoden set to a potpourri of short minimalist pieces by Philip Glass, Luke Howard, Kirrill Richter, Hans Zimmer, and Peter Gregson.

Esteban Hernandez, wearing a sparkly gold shirt, felt like the master of ceremonies for the seven-movement work, leaping and moving frantically throughout even when the music was a mournful solo cello piece.

The abstract scenario had something to do with the pandemic and its isolation, but there was a heap of sexiness too, provided by Angelo Greco among others.

On its own terms, the piece is a major success. Congratulations to choreographer Dwight Roden (and his assistant Clifford Williams, top left in the gold suit), dancers Benjamin Freemantle and WanTing Zhao (above center), and cello soloist Eric Sung who were all superb.

The neo-Balanchine ballet's other highlight was the partnering of longtime principal dancers Yuan Yuan Tan, who premiered the role in San Francisco over 20 years ago, and Tiit Helmets. (All production photos are by Erik Tomasson.)

The second work was Finale Finale, a world premiere ballet by my favorite current choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, who has been nurtured by Tomasson with commissions in San Francisco for the last two decades. It is a gorgeously loose, complex, and funny piece set to Darius Milhaud's 1920 Le Boeuf sur le toit (literally The Ox on the Roof) which started out as a score for a Chaplin silent short and ended up as a ballet with a scenario by Cocteau. Milhaud had just spent two years working as a diplomatic secretary in Brazil, and the music is filled with danceable Latin tunes that dissolve into astringent fogs before bouncing back again. The orchestra gave a wonderful performance and the choreography was delightfully ambiguous, sometimes in lockstep with the music and other times doing its own thing altogether.

The ballet was created for seven dancers, including Dores Andre and Joseph Walsh (above), Isabella Devivo and Benjamin Freemantle, and the amusing trio of Elizabeth Powell, Cavan Conley, and Esteban Hernandez. They were all superb and seemed to be enjoying themselves immensely. The ballet is an instant classic.

The third work for a huge company contingent was The Promised Land, another world premiere by choreographer Dwight Rhoden set to a potpourri of short minimalist pieces by Philip Glass, Luke Howard, Kirrill Richter, Hans Zimmer, and Peter Gregson.

Esteban Hernandez, wearing a sparkly gold shirt, felt like the master of ceremonies for the seven-movement work, leaping and moving frantically throughout even when the music was a mournful solo cello piece.

The abstract scenario had something to do with the pandemic and its isolation, but there was a heap of sexiness too, provided by Angelo Greco among others.

On its own terms, the piece is a major success. Congratulations to choreographer Dwight Roden (and his assistant Clifford Williams, top left in the gold suit), dancers Benjamin Freemantle and WanTing Zhao (above center), and cello soloist Eric Sung who were all superb.

Friday, April 01, 2022

Van Ness Red Bus Lane Opens, Finally

"Notice anything new?" the signage asked, and I thought, "Yes, the construction equipment and potholes and broken sidewalks that have been part and parcel of this Van Ness public works project for what feels like decades is gone." Hurray.

As somebody who vowed never to get a driver's license as a teenager growing up in Southern California, and who has been depending on MUNI for close to 50 years for local transportation, I was completely ambivalent about this huge construction project.

The idea was to forge a middle lane for fast-moving buses in a large boulevard historically devoted to car culture. (It's still on maps as an extension of Highway 101 from the Golden Gate Bridge.) My ambivalence stems from watching the grotesquely overtime and overbudget project over the years where huge construction crews would arrive for two weeks of work, and then would disappear for months, leaving a different mess behind each time.

I love public transportation public works initiatives, but the smell of graft and incompetence has hung over this project for years as it kept extending its deadlines and destroying the entire small business corridor over a decade. The "It's A Small World" public art at some of the bus stops just adds insult to injury.

But that's enough whining. We took a 49 bus on Opening Day this afternoon, north on Van Ness Avenue from McAllister Street to Pacific Street and the smooth ride took about 7 minutes rather than the usual 10 to 20 minutes. "What do you think of it?" my partner Austin asked. "I like it," was the reply. Now bring back the 47 bus, MUNI, so the 49 is not the only line taking advantage of this snazzy new lane that cost way too much in time and money.

As somebody who vowed never to get a driver's license as a teenager growing up in Southern California, and who has been depending on MUNI for close to 50 years for local transportation, I was completely ambivalent about this huge construction project.

The idea was to forge a middle lane for fast-moving buses in a large boulevard historically devoted to car culture. (It's still on maps as an extension of Highway 101 from the Golden Gate Bridge.) My ambivalence stems from watching the grotesquely overtime and overbudget project over the years where huge construction crews would arrive for two weeks of work, and then would disappear for months, leaving a different mess behind each time.

I love public transportation public works initiatives, but the smell of graft and incompetence has hung over this project for years as it kept extending its deadlines and destroying the entire small business corridor over a decade. The "It's A Small World" public art at some of the bus stops just adds insult to injury.

But that's enough whining. We took a 49 bus on Opening Day this afternoon, north on Van Ness Avenue from McAllister Street to Pacific Street and the smooth ride took about 7 minutes rather than the usual 10 to 20 minutes. "What do you think of it?" my partner Austin asked. "I like it," was the reply. Now bring back the 47 bus, MUNI, so the 49 is not the only line taking advantage of this snazzy new lane that cost way too much in time and money.