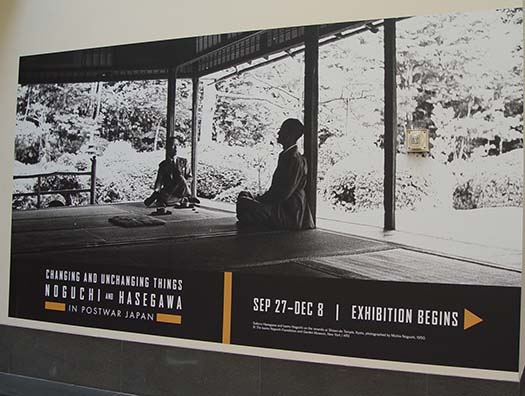

There is a wonderful exhibit at the Asian Art Museum featuring the work of Isamu Noguchi (mostly sculpture) and Saboru Hasegawa (mostly woodblock prints).

Born in the first decade of the 20th century, they both had complicated, interesting artistic lives that fused traditional Asian forms with modern Western art. Both studied with artists in Paris during the early 1930s and both were locked up in internment camps during World War Two, Hasegawa in Japan for his pacifism and Noguchi in the United States for his ethnicity. According to an informative article by Tony Bravo about the exhibit in the SF Chronicle, "During Noguchi’s 1950 tour of Japan, Noguchi traveled to the country in an attempt to reconnect with his father’s Japanese family roots. Hasegawa, then working as a teacher, was fluent in English and became Noguchi’s tour guide...As the artists toured Buddhist sites and traditional gardens, and met traditional art makers in Japan, an exchange developed between them."

The friendship was deep and productive, and this exhibit focuses on work created by both of them during the seven years before Hasegawa's early death at age 50 of cancer in San Francisco, where he was teaching at the College of Arts and Crafts, a job he secured through the intervention of Noguchi and Alan Watts, author of The Way of Zen.

The exhibit feels a bit off-balance at first because Noguchi's sculptures dominate the two rooms...

...making Hasegawa's monochromatic prints feel somewhat like literal wallflowers.

On return visits to the show, it was the Hawegawa prints that stood out for me. Some of them looked like a Japanese woodblock version of Joan Miró, with spareness and complexity residing in the same frame.

Though it's a small exhibit, I am still discovering new details and what feels like completely new works with each visit.

It closes on Sunday, December 8th, so if you have a chance, do check it out in the next couple of weeks.

If you are in San Francisco for the holiday weekend, this Sunday, December 1st is a free admission day at the Asian Art Museum. Check it out and you can see my friend James Parr's favorite Noguchi sculpture above, the 1950 My Mu.

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

Thursday, November 21, 2019

Hansel and Gretel at the SF Opera

Cannibalism. Serial Murder. Child abuse. Starvation. Sugar. Even by the the dark standards of Grimm's Children's and Household Tales, Hansel and Gretel has always struck me as especially brutal. Thomas Pynchon wrote a scatalological riff on the fairy tale in his novel, Gravity's Rainbow, and the Yugoslavian film director Dušan Makavejev used it as a subtext in his outrageous 1974 Sweet Movie. I've always been curious what the late 19th century German composer Englebert Humperdinck did with the tale in his popular opera, and finally got to see it for the first time at the San Francisco Opera last Sunday afternoon. (Sasha Cooke and Heidi Stober above as Hansel and Gretel, all photos by Cory Weaver.)

SF Opera produced Hansel and Gretel for three straight seasons, 1929-1932, and then waited 70 years to produce it again in 2002. I missed that production which was widely praised for its dark, surrealist spin, but 17 years later another British take has arrived at the War Memorial Opera House. First off, the opera itself turns out to be musically great, an intriguing mixture of German folk music and Wagnerian orchestral density.

Hansel and Gretel are written for two sopranos, and both Sasha Cooke and Heidi Strober were at the top of their performing game, sounding marvelous and looking convincing as outsized children trying to survive food deprivation, a hateful mother, and a scary haunted forest where a witch wanted to eat them after a good roasting in her oven.

The British production designer and director of this show, Antony McDonald, creates stunning visual moments but I questioned some of his staging decisions. When the two babes in the wood are being threatened in Act II, they are protected by 14 guardian angels during the most beautiful extended orchestral music of the opera. In this version, the guardians are Disneyfied fairy tale characters which was a little too cutesy and meta for its own good. I immediately thought of Rob Lowe and Snow White at the 1989 Academy Awards which took me out of the opera completely. One of the few positive mythologies I took from a quasi-Christian upbringing was the idea of Guardian Angels, and I felt very cheated not seeing them.

In the final act, Hansel and Gretel discover the witch's house which in this production is modeled after Hitchcock's Psycho house.

That would be fine, except that there is an extended dramatic sequence where the children are eating sugary treats that make up the house, but here it just looked like they were eating wood. It's not good to be this literal around fantasy, but a certain surreal consistency counts. That also goes for the death of the witch, which includes the satisfying physical detail of making her inspect something in the oven, then PUSHING HER IN. That doesn't happen in this production either.

None of this particularly matters, because the orchestra under Christopher Franklin sounds so exquisite, and the performers are all wonderful, including Robert Brubaker above as a non-binary witch, along with Alfred Walker as Father and Mary Evelyn Hangley stepping in at the last minute for an indisposed MIchaela Martens as the evil Mother. "Work or starve" is her Act ! injunction towards her children and it feels utterly resonant right now.

SF Opera produced Hansel and Gretel for three straight seasons, 1929-1932, and then waited 70 years to produce it again in 2002. I missed that production which was widely praised for its dark, surrealist spin, but 17 years later another British take has arrived at the War Memorial Opera House. First off, the opera itself turns out to be musically great, an intriguing mixture of German folk music and Wagnerian orchestral density.

Hansel and Gretel are written for two sopranos, and both Sasha Cooke and Heidi Strober were at the top of their performing game, sounding marvelous and looking convincing as outsized children trying to survive food deprivation, a hateful mother, and a scary haunted forest where a witch wanted to eat them after a good roasting in her oven.

The British production designer and director of this show, Antony McDonald, creates stunning visual moments but I questioned some of his staging decisions. When the two babes in the wood are being threatened in Act II, they are protected by 14 guardian angels during the most beautiful extended orchestral music of the opera. In this version, the guardians are Disneyfied fairy tale characters which was a little too cutesy and meta for its own good. I immediately thought of Rob Lowe and Snow White at the 1989 Academy Awards which took me out of the opera completely. One of the few positive mythologies I took from a quasi-Christian upbringing was the idea of Guardian Angels, and I felt very cheated not seeing them.

In the final act, Hansel and Gretel discover the witch's house which in this production is modeled after Hitchcock's Psycho house.

That would be fine, except that there is an extended dramatic sequence where the children are eating sugary treats that make up the house, but here it just looked like they were eating wood. It's not good to be this literal around fantasy, but a certain surreal consistency counts. That also goes for the death of the witch, which includes the satisfying physical detail of making her inspect something in the oven, then PUSHING HER IN. That doesn't happen in this production either.

None of this particularly matters, because the orchestra under Christopher Franklin sounds so exquisite, and the performers are all wonderful, including Robert Brubaker above as a non-binary witch, along with Alfred Walker as Father and Mary Evelyn Hangley stepping in at the last minute for an indisposed MIchaela Martens as the evil Mother. "Work or starve" is her Act ! injunction towards her children and it feels utterly resonant right now.

Sunday, November 17, 2019

SOFT POWER at SFMOMA

SOFT POWER, an ambitious show of new artwork from 20 international artists, just opened on two floors at SFMOMA and I'm afraid it was underwhelming.

According to the exhibition's website, the show is supposed to be political: "Appropriated from the Reagan-era term used to describe how a country’s “soft” assets such as culture, political values, and foreign policies can be more influential than coercive or violent expressions of power, the title contemplates the potential of art and offers a provocation to the public to exert their own influence on the world."

It continues: "Taken together, the works in SOFT POWER demonstrate what cultural theorist and filmmaker Manthia Diawara has called a solidarity between intuitions — a concept that acknowledges the complexity, darkness, and opacity from which our reality emerges — that expresses the poetry and imagination of our differences."

It doesn't get much more amorphously artspeak than that.

There are probably some very good artists in the exhibition, but the context doesn't do them any favors. As my friend Austin said, "This is no time to be timid with political art, either go big or go home."

A couple of artists felt the same way, including Minerva Cuevas from Mexico City with The Discovery of invisible nature, her wonderful mural wall at the entrance to the 7th floor galleries.

So did Xaviera Simmons from New York City who created a wall-size riff on Jacob Lawrence's Migration series from the 1940s.

It's entitled, They're All Afraid, All of Them, That's It! They're All Southern! The Whole United States Is Southern!

However, most of the conceptual art was indeed timid, like Brazilian Cinthia Marcelle's There Is No More Place in This Place with its messing up of ceiling tiles. According to the wall text, "For the artist, the grid structure that supports these tiles represents the patriarchal system that has governed for as long as we can recall. As expressed through architecture, this felt patriarchy has shaped our experiences, memories, and movements." The irony, of course, is that this exhibition and the latest expansion of the museum was primarily bankrolled by Charles Schwab, proud San Francisco Republican and patriarchy personified.

There is one truly great, striking work on the 4th floor: Jewel, a seven-minute film by the London artist Hassan Khan. I'm not going to ruin it by trying to describe the piece, so let's just say it involves Mideastern music, light, and two men dancing.

According to the exhibition's website, the show is supposed to be political: "Appropriated from the Reagan-era term used to describe how a country’s “soft” assets such as culture, political values, and foreign policies can be more influential than coercive or violent expressions of power, the title contemplates the potential of art and offers a provocation to the public to exert their own influence on the world."

It continues: "Taken together, the works in SOFT POWER demonstrate what cultural theorist and filmmaker Manthia Diawara has called a solidarity between intuitions — a concept that acknowledges the complexity, darkness, and opacity from which our reality emerges — that expresses the poetry and imagination of our differences."

It doesn't get much more amorphously artspeak than that.

There are probably some very good artists in the exhibition, but the context doesn't do them any favors. As my friend Austin said, "This is no time to be timid with political art, either go big or go home."

A couple of artists felt the same way, including Minerva Cuevas from Mexico City with The Discovery of invisible nature, her wonderful mural wall at the entrance to the 7th floor galleries.

So did Xaviera Simmons from New York City who created a wall-size riff on Jacob Lawrence's Migration series from the 1940s.

It's entitled, They're All Afraid, All of Them, That's It! They're All Southern! The Whole United States Is Southern!

However, most of the conceptual art was indeed timid, like Brazilian Cinthia Marcelle's There Is No More Place in This Place with its messing up of ceiling tiles. According to the wall text, "For the artist, the grid structure that supports these tiles represents the patriarchal system that has governed for as long as we can recall. As expressed through architecture, this felt patriarchy has shaped our experiences, memories, and movements." The irony, of course, is that this exhibition and the latest expansion of the museum was primarily bankrolled by Charles Schwab, proud San Francisco Republican and patriarchy personified.

There is one truly great, striking work on the 4th floor: Jewel, a seven-minute film by the London artist Hassan Khan. I'm not going to ruin it by trying to describe the piece, so let's just say it involves Mideastern music, light, and two men dancing.

Sunday, November 10, 2019

Bay Area Science Festival at the Ballpark

Last Saturday on a walk along San Francisco's Embarcadero, we stumbled on the Bay Area Science Festival being held for free at the ballpark.

We weren't sure if it was going to be a Science Fair with elaborate booths put together by kids and their parents...

...but it turned out to be an adult educational outreach for families...

...organized by UCSF.

There were Stomp Rockets, a fabulous term I had never encountered...

...along with young men putting together Robots...

...that could play with each other.

The best swag was at the NASA booth...

...along with the best poseable spaceship photo background.

We weren't sure if it was going to be a Science Fair with elaborate booths put together by kids and their parents...

...but it turned out to be an adult educational outreach for families...

...organized by UCSF.

There were Stomp Rockets, a fabulous term I had never encountered...

...along with young men putting together Robots...

...that could play with each other.

The best swag was at the NASA booth...

...along with the best poseable spaceship photo background.

Saturday, November 09, 2019

The Marriage of Figaro at SF Opera

Last month the San Francisco Opera offered a new production of Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro, which I caught up with in its penultimate performance. Let me echo the praise of others, for the production design of Erhard Rom, the costume design of Constance Hoffman, the direction by Michael Cavanagh, the singing of a tightly-knit ensemble cast, and the conducting by Henrik Nánási. (Pictured above are Catherine Cook as Marcellina and Jeanine De Bique as Susanna, singing an improbably beautiful duet that is actually a cat fight. All photos by Cory Weaver.)

The production's massive American Colonial estate can be arranged in a remarkably versatile set of arrangements, which is a relief because the same set will be used for forthcoming productions of Cosi fan Tutte next year and Don Giovanni in the subsedquent year. Cosi will be set in the 1930s and Don Giovanni in a dystopian American future (I wonder if there will be zombies.)

The Marriage of Figaro was written about contemporary life when it opened in Vienna in the late 18th century, and this production has stayed with the same time period, moving the setting from Spain to Colonial America. The original play by the French playwright Beaumarchais had to move the location from France to Spain to get past the royal censors of his time, so the geographic move to the U.S. feels perfectly fine, but it does bring into relief a particular ugliness in the story. The long play/opera is essentially a sex farce where most of the characters are thwarting the plan of an aristocrat who wants to have carnal relations with his servant's fiance. There's even a French term for it, droit du seigneur, defined as "the supposed right claimable by a feudal lord to have sexual relations with the bride of a vassal on her first night of marriage." (Pictured above is Michael Sumuel as the wily vassal Figaro.)

Every time I have seen the opera this particular detail always struck me as barbaric, ancient and foreign, but moving the story to the United States unintentionally offered a "Hey, remember slavery and rape?" moment, emphasized by the blind casting of Michael Sumuel as Figaro and Jeanine De Bique as Susanna.

I love blind (to race) casting, and in this case it made the already absurdist Act Three scene of parental discovery even more absurd, when Figaro learns his two tormentors (the marvelous Catherine Cook as Marcellina and James Creswell as Bartolo) are actually his long-lost parents. But the specter of American slavery persists in the background without being addressed by the production, which feels like a failure of imaginative nerve.

The Count can be played in many ways, from sympathetic lecher to a philandering villain, and this production leaned more towards the latter. Baritone Levent Molnar's portrayal kept bringing to mind Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo movement which made a lot of the farcical shenanigans feel tone deaf. Nicole Heaston as his ignored Countess was convincingly sad while singing one stretch of beautiful music after another.

Mozart's music in this nearly four-hour opera is as great as anything he ever composed, which is why it will live forever. One of the best voices in the cast was Italian mezzo-soprano Serena Malfi as the teenage horny toad who triggers most of the farcical situations of the plot.

Also worthy of mention is Natalie Image as Barbarina, one of Cherubino's many love objects, who in this production has much of her usually cut role restored. I've seen this opera at least a dozen times over the years, and this was the first time I realized she was the daughter of the drunken gardener, Antonio. It's all one big, screwed-up family with wealth inequality baked in.

The production's massive American Colonial estate can be arranged in a remarkably versatile set of arrangements, which is a relief because the same set will be used for forthcoming productions of Cosi fan Tutte next year and Don Giovanni in the subsedquent year. Cosi will be set in the 1930s and Don Giovanni in a dystopian American future (I wonder if there will be zombies.)

The Marriage of Figaro was written about contemporary life when it opened in Vienna in the late 18th century, and this production has stayed with the same time period, moving the setting from Spain to Colonial America. The original play by the French playwright Beaumarchais had to move the location from France to Spain to get past the royal censors of his time, so the geographic move to the U.S. feels perfectly fine, but it does bring into relief a particular ugliness in the story. The long play/opera is essentially a sex farce where most of the characters are thwarting the plan of an aristocrat who wants to have carnal relations with his servant's fiance. There's even a French term for it, droit du seigneur, defined as "the supposed right claimable by a feudal lord to have sexual relations with the bride of a vassal on her first night of marriage." (Pictured above is Michael Sumuel as the wily vassal Figaro.)

Every time I have seen the opera this particular detail always struck me as barbaric, ancient and foreign, but moving the story to the United States unintentionally offered a "Hey, remember slavery and rape?" moment, emphasized by the blind casting of Michael Sumuel as Figaro and Jeanine De Bique as Susanna.

I love blind (to race) casting, and in this case it made the already absurdist Act Three scene of parental discovery even more absurd, when Figaro learns his two tormentors (the marvelous Catherine Cook as Marcellina and James Creswell as Bartolo) are actually his long-lost parents. But the specter of American slavery persists in the background without being addressed by the production, which feels like a failure of imaginative nerve.

The Count can be played in many ways, from sympathetic lecher to a philandering villain, and this production leaned more towards the latter. Baritone Levent Molnar's portrayal kept bringing to mind Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo movement which made a lot of the farcical shenanigans feel tone deaf. Nicole Heaston as his ignored Countess was convincingly sad while singing one stretch of beautiful music after another.

Mozart's music in this nearly four-hour opera is as great as anything he ever composed, which is why it will live forever. One of the best voices in the cast was Italian mezzo-soprano Serena Malfi as the teenage horny toad who triggers most of the farcical situations of the plot.

Also worthy of mention is Natalie Image as Barbarina, one of Cherubino's many love objects, who in this production has much of her usually cut role restored. I've seen this opera at least a dozen times over the years, and this was the first time I realized she was the daughter of the drunken gardener, Antonio. It's all one big, screwed-up family with wealth inequality baked in.

Monday, November 04, 2019

Pop Up Drag Dancing for the Dead

My favorite San Francisco busker is Shane Zal-Diva, a drag queen who sinuously dances to recorded music in front of the Ferry Building on occasion.

On last Saturday afternoon's Dia de los Muertos, she was attired for the occasion...

...and used it for a political statement...

...on a retablo mourning transgender women who have been murdered.

She calls herself the Pop Up Drag Queen on Facebook, and her public performance art is amusing and inspiring.

On last Saturday afternoon's Dia de los Muertos, she was attired for the occasion...

...and used it for a political statement...

...on a retablo mourning transgender women who have been murdered.

She calls herself the Pop Up Drag Queen on Facebook, and her public performance art is amusing and inspiring.

Sunday, November 03, 2019

Semana de Los Muertos at the SF Symphony

Last Friday at Davies Hall one of the translucent acoustic tiles decided to join the musicians onstage before the all-Russian concert of Prokofiev's Piano Concerto #1 and Shostakovich's Symphony #7 "Leningrad".

The musicians looked startled at the intrusion...

...but stage management managed to hoist the thing back into place without too much of a delay.

Prokofiev's first piano concerto is a 15-minute barn-burner that the composer wrote in 1911 while still at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. It's one of my favorite pieces of music, with an abundance of catchy melodies and intense rhythmic energy. Unfortunately, the Ukranian soloist Alexander Gavrylyuk above made a hash of it, playing too fast and eliding all the fun.

After intermission, debuting guest conductor Karina Canellakis led the huge orchestra in Shostakovich's Symphony #7. The 80-minute work was written during World War Two, some of it in Leningrad (the renamed St. Petersburg) during the Nazi siege on that city which eventually killed over a million people through bombing, starvation, and cold.

The symphony is a sprawling, four-movement work that was "lavishly praised in wartime, then largely dismissed in its aftermath," according to liner notes by Richard Whitehouse for Vasily Petrenko's Shostakovich set. It's still being largely dismissed, with the SF Chronicle's Joshua Kosman writing in his review of this performance, "The music can often meander around slowly, this way and that, like a drunk looking for a missing set of keys."

In the distant past, I often found Shostakovich's music bombastic and meandering, but after enough great performances at the SF Symphony with young conductors like Urbanski and Petrenko, I changed my mind and always give Shostakovich the benefit of the doubt. Petrenko has an interesting quote: "I've met a few people still alive who listened to all the first broadcasts of these war symphonies [#7-#9] and they've told me how they were sitting in the kitchen listening to the Seventh, and what a powerful emotional effect it had on them; the Eighth was more challenging, but they understood it; after the Ninth they got up in silence and left the room. The message was so clear: we may have won the war, but the same guy [Stalin} is in charge."

The young American conductor Karina Cannellakis led a performance last week that was alternately gorgeous and meandering. The long first movement, where an earworm of a banal war march intrudes into a lively, peaceful scene sounded more like Bolero than the dark, grotesquely satirical joke it is meant to envision, and she found it impossible to pull all the disparate moods of the long symphony together. However, the orchestra sounded magnificent, especially percussionist Jacob Nissly and the entire 23-person brass section above. It was powerful hearing the work live for the first time and I look forward to hearing it again with a conductor who can pull it all together.

The musicians looked startled at the intrusion...

...but stage management managed to hoist the thing back into place without too much of a delay.

Prokofiev's first piano concerto is a 15-minute barn-burner that the composer wrote in 1911 while still at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. It's one of my favorite pieces of music, with an abundance of catchy melodies and intense rhythmic energy. Unfortunately, the Ukranian soloist Alexander Gavrylyuk above made a hash of it, playing too fast and eliding all the fun.

After intermission, debuting guest conductor Karina Canellakis led the huge orchestra in Shostakovich's Symphony #7. The 80-minute work was written during World War Two, some of it in Leningrad (the renamed St. Petersburg) during the Nazi siege on that city which eventually killed over a million people through bombing, starvation, and cold.

The symphony is a sprawling, four-movement work that was "lavishly praised in wartime, then largely dismissed in its aftermath," according to liner notes by Richard Whitehouse for Vasily Petrenko's Shostakovich set. It's still being largely dismissed, with the SF Chronicle's Joshua Kosman writing in his review of this performance, "The music can often meander around slowly, this way and that, like a drunk looking for a missing set of keys."

In the distant past, I often found Shostakovich's music bombastic and meandering, but after enough great performances at the SF Symphony with young conductors like Urbanski and Petrenko, I changed my mind and always give Shostakovich the benefit of the doubt. Petrenko has an interesting quote: "I've met a few people still alive who listened to all the first broadcasts of these war symphonies [#7-#9] and they've told me how they were sitting in the kitchen listening to the Seventh, and what a powerful emotional effect it had on them; the Eighth was more challenging, but they understood it; after the Ninth they got up in silence and left the room. The message was so clear: we may have won the war, but the same guy [Stalin} is in charge."

The young American conductor Karina Cannellakis led a performance last week that was alternately gorgeous and meandering. The long first movement, where an earworm of a banal war march intrudes into a lively, peaceful scene sounded more like Bolero than the dark, grotesquely satirical joke it is meant to envision, and she found it impossible to pull all the disparate moods of the long symphony together. However, the orchestra sounded magnificent, especially percussionist Jacob Nissly and the entire 23-person brass section above. It was powerful hearing the work live for the first time and I look forward to hearing it again with a conductor who can pull it all together.